2025 British Grand Prix - All You Need to Know

The Formula 1 circus returns to Silverstone for the 2025 British Grand Prix -- a race steeped in history and significance. This year's event coincides with the 75th anniversary of the World Championship's inaugural round, which was held right here at Silverstone on May 13, 1950 . Often dubbed the "home of British motorsport," Silverstone's fast and flowing layout has been a permanent fixture on the F1 calendar since 1987, after earlier years shared with Aintree and Brands Hatch . The circuit's flat airfield origins belie the high-speed thrills it produces -- from legendary corners like Copse and Maggots/Becketts to its passionate capacity crowds (a record 480,000 fans attended over four days last year) . This is also a home race for many: eight of ten teams have bases in the UK, and four current drivers are British, adding extra buzz and support in the grandstands. As F1 reaches the halfway point of 2025, all eyes turn to Silverstone for what promises to be another classic showdown on this hallowed ground.

Circuit Characteristics and Challenges

Silverstone is renowned as one of the fastest circuits on the calendar, demanding a well-balanced car and courageous driving. Its 5.891 km lap length makes it the fifth-longest F1 track (trailing Spa, Jeddah, Las Vegas, and Baku) . The circuit features 18 turns -- many of them high-speed sweepers that push drivers and tyres to the limit. Iconic sequences like Maggotts--Becketts--Chapel (Turns 10--14) are taken at rapid pace, generating sustained lateral G-forces exceeding 5g . In fact, Silverstone's combination of long, fast corners means lateral forces and overall tyre stress reach the maximum level of any track on Pirelli's severity index . By contrast, the circuit's few slow corners and long straights make traction and braking demands only moderate in comparison . This fundamental character -- ultra-fast bends linked by decent straights -- puts a premium on aerodynamic downforce and stable high-speed balance.

From an engineering standpoint, teams face the challenge of optimizing for Silverstone's split personality. On one hand, the track rewards extreme downforce to carry speed through the sweeping bends (Copse, Maggotts, etc.). On the other hand, there are several straights (the Hangar and Wellington straights, in particular) where power and low drag can pay dividends on top speed . The car setup, therefore, tends to be a high-downforce package, as the time gained in corners outweighs time lost on the straights -- but finding the right wing level and suspension stiffness is key to maintain stability through quick direction changes. Silverstone's former life as an airfield means it is very flat (virtually no significant elevation changes), but its open layout leaves it exposed to winds. Sudden gusts can upset a car's aerodynamic balance mid-corner, a notorious difficulty especially through Maggotts/Becketts where a tailwind or crosswind can drastically alter grip.

Mechanical grip is still important in the few slow sections (like the Turn 3--4 complex and the Turn 16--17 chicane), so teams cannot neglect suspension tuning and differential settings. The circuit's surface is relatively abrasive and well-used -- numerous racing series and track events keep the tarmac rubbered-in. Grip levels are generally high (especially as more rubber is laid down), but the aggressive asphalt plus high-energy loads lead to significant tyre wear and thermal degradation. The left-front tyre, in particular, is heavily stressed (nearly all the fastest corners are right-handers, putting big loads through the front-left) . We've seen this manifest dramatically in the past -- for example, multiple front-left tyre failures in the 2013 race and Lewis Hamilton's late puncture in 2020. Teams will be mindful of managing tyre temperatures to avoid blistering or excessive wear over long stints.

Finally, Silverstone is known for its wide track and ample run-offs, which encourage drivers to push the limits. While track limits aren't usually as controversial here as at some circuits, exceeding the kerbs at Copse or Stowe can still result in lap times being deleted if all four wheels go beyond the line. The modern Silverstone layout, introduced in 2010 (Arena section) and the new pit straight in 2011, has produced excellent racing in recent years -- its mix of flat-out kinks and heavy braking zones tends to keep cars within range, setting the stage for wheel-to-wheel action.

Pit Lane and Technical Features

Silverstone's pit lane is among the longer ones in F1, running from the entry before the final Club corner to the exit after Turn 1 (Abbey). A routine pit stop here costs roughly 19.9 seconds of race time (including about 2.5s stationary) -- only a little shorter than Spielberg's pit loss. This relatively high time loss means teams will be cautious about extra stops unless they are confident of a significant pace offset on fresh tyres. The pit entry is straightforward (a late peel-off before the last chicane), but the exit feeds directly into the high-speed Turn 1 line, so drivers rejoining must be careful to stay within the blend line and up to speed.

Notably, Silverstone has become a leader in sustainability initiatives for race venues. In 2023, the circuit launched its "Shift to Zero" program aimed at dramatically reducing the event's carbon footprint. Over 2,700 solar panels were installed on the Wing pit building, supplying more than 10% of the venue's power . All on-site generators under Silverstone's control were switched to hydrotreated vegetable oil (HVO) biofuel, cutting generator emissions by 90% . By using renewable energy sources and other green measures (such as EV charging stations and eliminating single-use plastics), the 2023 British GP operated entirely on alternative green energy . These efforts earned Silverstone an environmental award and align with Formula 1's push toward net-zero by 2030. (In fact, Formula 1 trialed a similar sustainable power unit for the paddock at the 2023 Austrian GP , and Silverstone's initiative reinforces that direction.) Fans attending the Grand Prix will also have noticed improved recycling facilities and encouragement of public transport, as the circuit continues to innovate off-track as well as on it.

Key Corners

-

Turn 1 -- Abbey: A right-hand kink taken flat-out in modern F1 cars, Abbey kicks off the lap at tremendous speed . The run from pole to the Turn 1 apex is ~239 meters , so on Lap 1 we often see cars arrive almost side-by-side. In clear air, Abbey is easy flat; however, when following another car closely, the dirty air can make it touch-and-go to keep it flat . Any lift or instability here can cost momentum all the way through the opening sector. Drivers also have to be mindful on cold tyres at the start -- this corner has seen first-lap incidents (e.g. Zhou's rollover in 2022 occurred just after Abbey). A strong exit sets you up for the approach to Turn 3.

-

Turns 3--4 -- Village and The Loop: After the flat-out sweep of Turn 2 (Farm curve), the track funnels into Village, a tight right-hand hairpin (T3). This is a very hard braking zone coming off high speed -- an inviting spot for a lunge down the inside . Overtakes into Village are common on the opening lap and restarts. The corner itself is tricky: it has some camber, and if a driver out-brakes himself even slightly, he'll run wide. Exiting Village, drivers immediately flick left into The Loop (T4), an off-camber tight left. The Loop is one of the slowest corners on the circuit, and traction here is critical. Cars tend to experience wheelspin as they accelerate out onto Aintree corner and the Wellington Straight. It was at this complex in 2024 that Hamilton and Russell went side by side, each briefly off track, in a battle for the lead in damp conditions . Expect to see drivers positioning out of Village to either defend or spring an attack down the next straight.

-

Turn 6 -- Brooklands: After blasting down the Wellington Straight under DRS, drivers hit the brakes for Brooklands, a medium-speed left-hander (about 110--130 km/h at the apex). This is one of Silverstone's prime overtaking spots . A chasing car can slipstream and draft with DRS, then dive inside under braking. The braking zone is not perfectly straight, so it's easy to lock the front-left tyre while trail-braking into Brooklands -- something Jolyon Palmer notes as a common mistake here . If a driver runs too deep or locks up, the door opens for a cut-back pass. Successfully making the corner, drivers hug a late apex and quickly get over to set up for the next turn. Brooklands flows directly into the long right of Luffield, so carrying speed while still making the apex is a delicate balance.

-

Turn 7 -- Luffield: A long, tightening right-hander that feels endless to the drivers. Luffield is all about patience and traction -- the car tends to understeer mid-corner then oversteer on exit as the throttle comes in. It's important to get the car tucked in early and then modulate power to not run wide. Luffield's exit is critical because it leads onto the old start/finish straight (through the flat-out Turn 8 Woodcote). A poor exit here will leave a driver vulnerable to attack into Copse. Notably, Luffield is one of those corners where multiple lines can work; we sometimes see a driver taking a later apex to slingshot out with more speed, potentially setting up an overtake into the next section.

-

Turn 9 -- Copse: One of Formula 1's great corners. Copse is a right-hand bend taken at around 290 km/h in qualifying -- essentially on the edge of flat out. In the race with heavy fuel or in traffic, a slight breathe of the throttle or downshift might be needed, but it's still extremely fast. The approach is through the slight kink of Woodcote, and there's a pit entry to the left, but drivers commit to Copse almost blind. This corner demands total confidence; it's high-risk, high-reward. Despite ample asphalt runoff on the outside, any mistake at these speeds can have big consequences (as seen in the Hamilton/Verstappen clash at Copse in 2021). Staying within track limits is also policed here -- all four wheels beyond the exit kerb will invalidate a lap time. Copse is a challenge even solo, but following another car closely into it can rob you of downforce and send you wide. Overtaking through Copse is rare (only bold attempts, as in 2021), but setting up right behind someone here can pay off down the next straights.

-

Turns 10-14 -- Maggotts, Becketts, Chapel: Arguably the most famous sequence in F1, this series of rapid left-right-left-right bends is where aerodynamics and chassis balance reign supreme. Entering at Maggotts (T10, left), the cars are still doing over 250 km/h. A slight lift or dab of brakes sets the front end, then immediately flick right into Becketts 1 (T11), then left again for Becketts 2 (T12). By T12 the speed has bled off to about 180--200 km/h, and Chapel (T13/14) is a sweeping right that leads onto the Hangar Straight. The drivers describe this complex as a rhythmic "weave" through which any error compounds -- get Maggotts wrong and you'll be offline and slow all the way out of Chapel. The G-forces here are punishing; the rapid direction changes at high speed put huge strain on the neck and the tyres (up to 5g lateral each way ). It's imperative to "slow it down through the final part" of Becketts to nail the exit onto the straight . A good exit out of Chapel (T14) onto the Hangar Straight can set up an overtake into the next corner. The sequence is a spectator favorite -- seeing F1 cars dance through Maggotts-Becketts is truly breathtaking.

-

Turn 15 -- Stowe: At the end of the high-speed Hangar Straight, cars approach Stowe at over 300 km/h, then brake down to around 170 km/h to sweep through this downhill right-hander. With DRS assistance and tow, Stowe is a classic passing opportunity, as a chasing car can draft and pop out to out-brake the leader. The corner itself has a slightly late apex and falls away on exit. A defending driver often takes the inside line here, forcing the attacker to try the outside or attempt a switchback. Because Stowe's exit has generous runoff, drivers sometimes use all of it (and then some) -- this was another area of track limits monitoring in past years. On throttle out of Stowe, the track drops downhill toward the Vale chicane. Notably, in 2024, this is where Hamilton grabbed the lead from Russell using DRS and late braking on Lap 18 . Stowe's challenge is carrying as much speed as possible without running wide or compromising the next section.

-

Turns 16--18 -- Vale/Club: This is the final complex: a slow left-right chicane (Vale, T16 left, T17 right) leading immediately into the long right of Club (T18) which exits onto the main straight. After so much high-speed action, slowing down for Vale (roughly 100 km/h) is a big adjustment. Braking into Turn 16 is tricky because it's downhill -- easy to lock up a tyre here. The sequence is a last-gasp overtaking spot: a bold dive into Vale can work if the car ahead is struggling for grip, and we've seen plenty of battles here (including drivers going side-by-side through the chicane). Hitting the kerb at T16 can unsettle the car, so most avoid clobbering the inside too hard. Quickly, they change direction for the right-hander T17 and then accelerate through Club Corner (T18), which is a faster right where traction is key. Club's exit is critical for the start/finish straight and also where the pit entry splits off (to the left). In recent years, this section has also seen track-limit drama -- in 2023, a few times were deleted for running wide at the exit of Club, though gravel traps just beyond the kerb act as natural deterrent now. Accelerating out of Club, the lap is complete and the cars blast by the pits to cross the line.

In summary, Silverstone's corners range from some of the slowest on the calendar to some of the absolute fastest. It's this contrast -- stop-go hairpins into sweeping "balls-to-the-wall" bends -- that makes driving here such a challenge and a thrill. The drivers consistently rank this track among their favorites, citing the unique sensation of the high-speed sections. As Jolyon Palmer puts it: "Copse, Maggots and Becketts are where you feel G-force on your body that is pretty rare in Formula 1" . Mastering these key corners is crucial for a quick lap -- and for setting up the overtaking opportunities we'll discuss next.

Racing Considerations

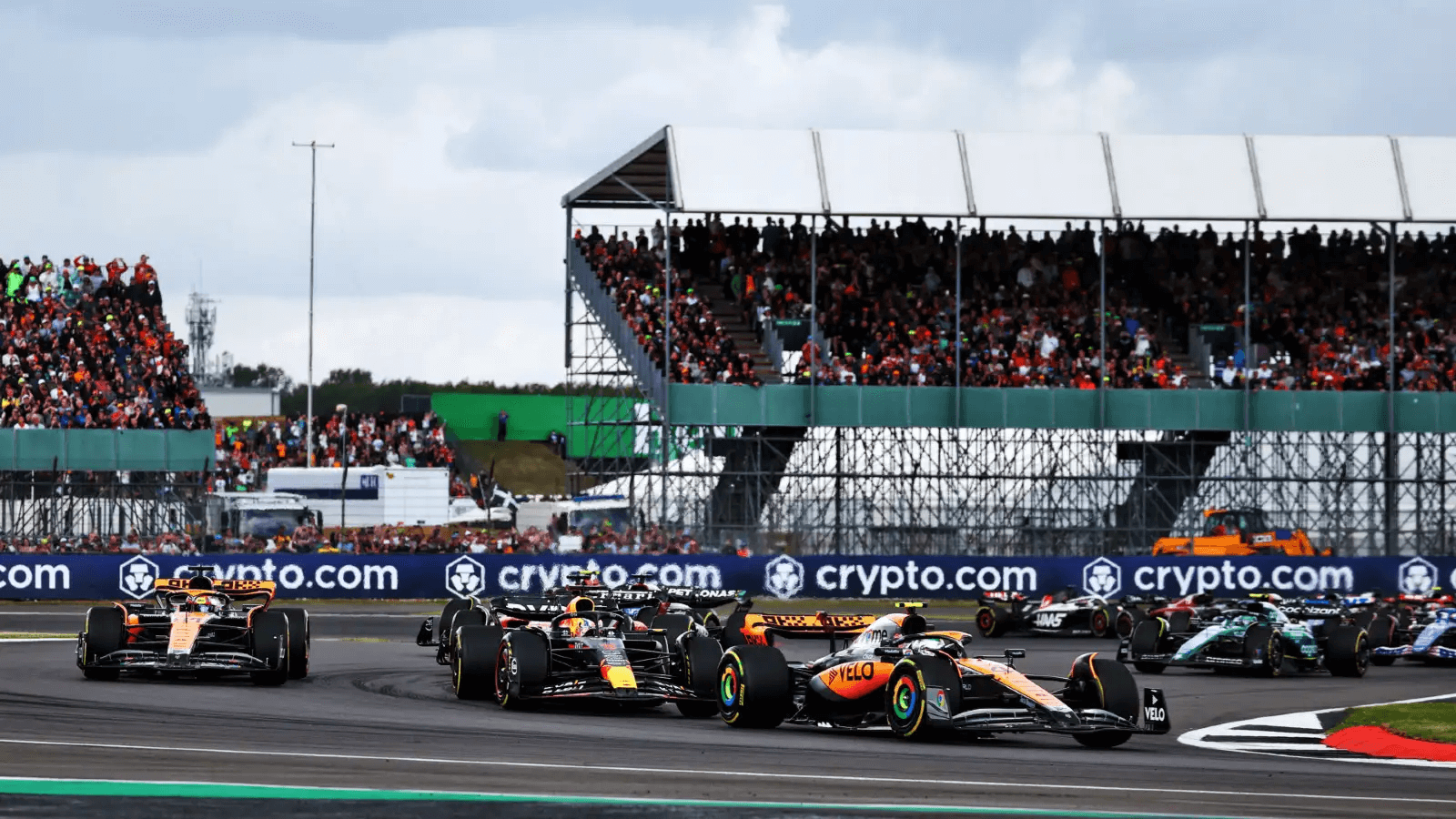

Silverstone typically produces high-quality racing thanks to its layout. The combination of multiple DRS zones and heavy braking into slower corners means drivers can follow and attempt passes, despite the disruption of turbulent air in the fast turns. The track is quite wide in many areas, allowing side-by-side battles (for example, the run through Luffield and onto the old pit straight can see cars alongside each other). In 2024 we were treated to a thrilling duel among Hamilton, Norris, Russell and Verstappen, with numerous lead changes and side-by-side moments in changing conditions .

One key talking point for racing at Silverstone is Safety Cars and race stoppages. Statistically, the British Grand Prix has a high chance of safety interventions. In fact, during the hybrid-turbo era (2014--present), a Safety Car has been deployed in all but one British GP, and there have been three red-flag stoppages in that period . (Notably, the dramatic first-lap crash in 2021 led to a red flag, and 2022's opening lap flip also caused a red flag.) The probability of a Safety Car is estimated around ~89% , one of the highest on the calendar. By contrast, Virtual Safety Cars are relatively rare at Silverstone -- only one VSC has occurred here since 2014 . This means teams often anticipate at least one full Safety Car, which can influence strategy calls (e.g. being ready to pit "for free" under a SC). Drivers, too, know that an aggressive move might be mitigated by a likely Safety Car to bunch the field later.

Track limits are generally less contentious than at circuits like the Red Bull Ring, but they still require attention. After some issues in 2022 and 2023, race control watches the exits of Copse, Stowe, and Club for any advantage gained by running wide. The addition of small gravel traps just beyond the kerbs at Stowe and Club has naturally reduced abuse -- drivers risk getting stuck or losing significant time if they run too far off. During qualifying in 2024, a few lap times were deleted (for instance, Oscar Piastri lost a front-row qualifying time for a millimeter over the line at Copse, illustrating the fine margins). In general, Silverstone's philosophy is to let the racing happen on track with minimal interference, but repeated offenders of track limits will still get penalties.

Overtaking at Silverstone is quite feasible -- the circuit was redesigned in part to improve racing, and it has paid off. While 2023's race saw about 50 on-track passes recorded , the average over the last five dry races is around 25 genuine overtakes per race (excluding starts/restarts) . This is roughly "mid-pack" in terms of overtaking frequency -- not a Monza-style slipstream fest, but certainly better than tight street circuits. Drivers often describe overtaking difficulty here as medium: you can pass, but you have to work for it and plan over several corners.

Tire degradation (or lack thereof) can also shape the racing. Silverstone's fast corners tend to punish the tyres, but the wear is often uniform enough that one-stop strategies are possible (so not everyone is forced to pit twice for performance reasons). When degradation is low and a one-stop is optimal (as it has often been in recent years when hardest compounds were used), track position becomes paramount -- which can sometimes make drivers more cautious to avoid giving up a place. However, as we'll discuss in the tyre section, 2025 sees a softer tyre allocation that could increase degradation and spice up strategy. Variable weather (common here) can also throw a wrench in the works -- a well-timed rain shower or a gust of wind can shuffle the order quickly.

Another factor at Silverstone is the crowd and home advantage. The British fans are famously loud and partisan, cheering on their heroes at every turn. Drivers often say they can hear the roar, especially if a Brit takes the lead or pulls an overtake. This energy can spur drivers to attempt bold moves in front of the grandstands (Luffield and the Wellington Straight grandstands, for instance, give a full view of an overtaking attempt into Brooklands). In 2024, the atmosphere was electric as three British drivers battled for the win; Hamilton credited the "amazing crowd energy" for helping him attack when it mattered. Expect a similar buzz this year, especially with Norris and Hamilton both in contention in the championship.

Finally, first-lap dynamics at Silverstone deserve mention. The short run to Abbey and the high-speed nature of Turn 1 mean that the field often stays tightly bunched through the first sector. It's not uncommon to see 3-wide moments into Village (Turn 3) on Lap 1. The opening sequence of corners can create traffic jams and even contact -- as cars check up for the slow Turns 3 and 4, opportunistic drivers may try to shoot gaps. The wide runoff at Turn 1 and Turn 3 has prevented some incidents, but as noted, we've had major crashes at the start here too. The pole-sitter isn't guaranteed to emerge in front after the first few corners due to these variables. Keep an eye on those opening laps -- they often set the tone for an action-packed race at Silverstone.

Overtaking Opportunities

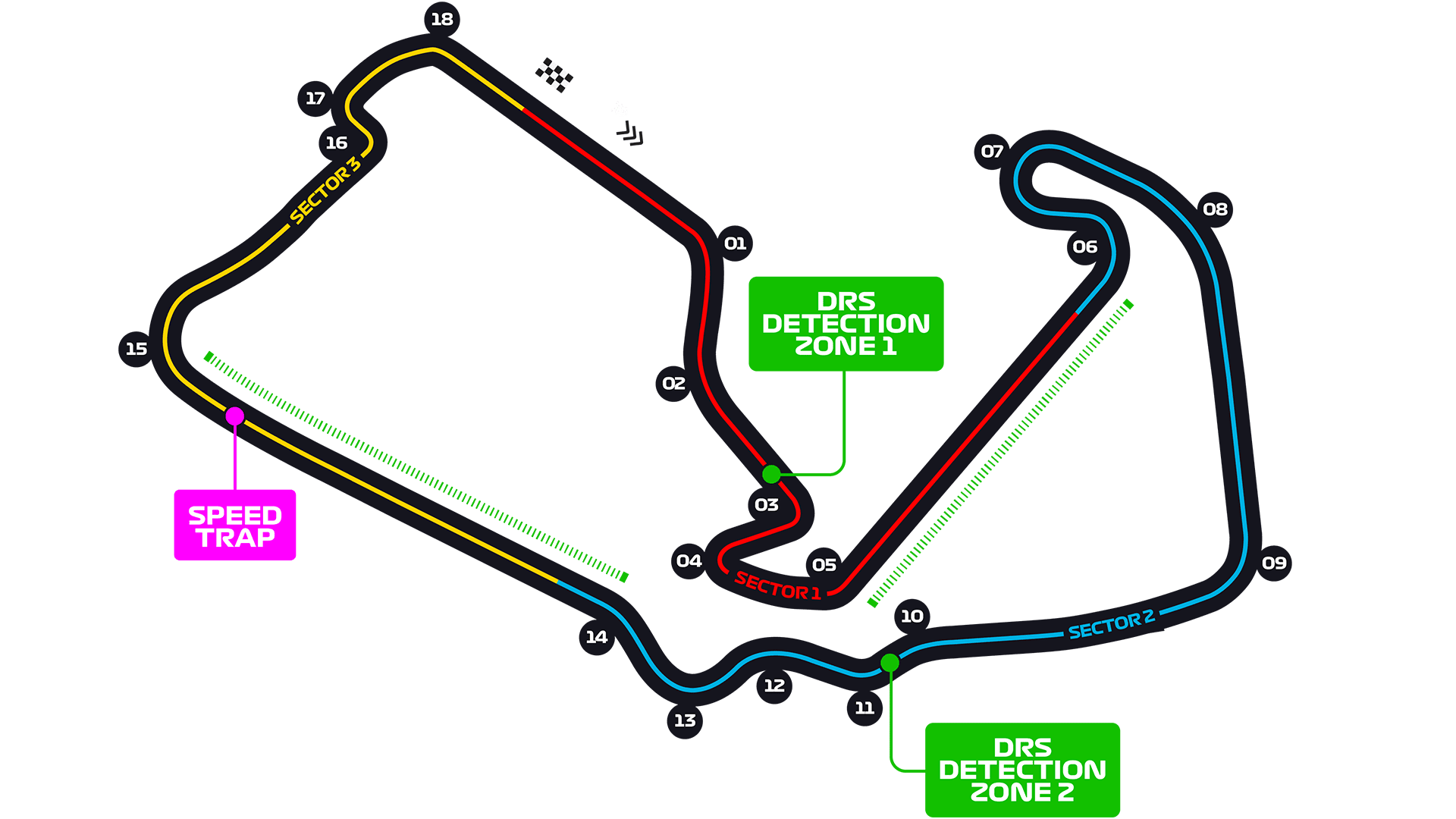

Silverstone offers several good overtaking opportunities, thanks to its combination of long straights and heavy braking zones. The track has two DRS zones in 2025 -- one on the Wellington Straight (between Aintree and Brooklands) and one on the Hangar Straight (between Chapel and Stowe) . These DRS zones are the primary facilitators of passing, allowing the pursuing car to close up before the braking zones.

-

Turn 3 (Village): While not a DRS zone entry, Turn 3 often sees action, especially on opening laps or after safety car restarts. A driver who gets a run through the flat-out Turns 1--2 may dive to the inside under braking for Village . Overtaking here is feasible if the car ahead is caught unawares or struggles on cold tyres. However, completing a pass into Village can leave you vulnerable on exit because the sequence leads into The Loop and then Wellington Straight. We sometimes see drivers attempt a move at T3 only to lose momentum and get re-passed on the straight immediately afterward. Still, it's a spot where bold moves happen -- think of it as a high-risk chance to surprise someone.

-

Turn 6 (Brooklands): This is one of the primary overtaking spots on the circuit. The Wellington Straight DRS allows a following car to close up and slingshot out of the slipstream. Brooklands' braking zone is long enough to out-brake an opponent from a few tenths back. We've seen many passes here, usually with a driver darting to the inside line before turn-in. As mentioned, Brooklands is also easy to lock a brake, so an attacking driver must judge it right to make the corner. If the attacking car makes it alongside at the apex, they can force the other car wide and seize the inside for Luffield. Conversely, a defending driver who holds the inside might slow both cars, leading to a potential over-under situation in Luffield. The majority of overtakes in recent British GPs occur in this DRS-to-Brooklands zone .

-

Turn 7 (Luffield) & Turn 8 (Woodcote): While not traditional overtaking corners in themselves, they can be part of an extended battle. If two cars go side-by-side through Brooklands, the fight often continues around Luffield. The car on the inside at Luffield (usually the one that started overtaking at Brooklands) can squeeze the other wide. Occasionally, drivers hang it around the outside of Luffield to get a better exit -- this can pay off by giving a run on the inside into Copse if they time it perfectly. Woodcote (Turn 8) is flat-out and typically single-file, but if someone had a poor exit from Luffield, an opportunistic driver might draw alongside into Copse (rare, but possible with a big pace delta or lapped traffic).

-

Turn 15 (Stowe): The end of the Hangar Straight is the other prime passing zone. With DRS and the natural tow, a chasing car can gain a significant closing speed. We often see passes initiated here -- either outright before the corner or by outbreaking into Stowe's entry. Stowe is wide on entry, so multiple lines are available. A classic move is to fake outside then dive inside under braking. If a driver successfully passes into Stowe, they need to quickly consolidate because the next sequence (Vale) comes up fast. If they only get alongside through the corner, they might have the inside for the chicane. Stowe passes are exciting because of the high approach speed -- committing to a move here requires confidence in your brakes and tyres. In 2024, Hamilton made a critical DRS pass on Russell for the lead into Stowe , illustrating how pivotal this corner can be.

-

Turns 16/17 (Vale Chicane): While DRS doesn't directly precede this section (the detection is before Stowe and activation after Turn 14 is not applicable), the Vale/Club complex can still offer an overtaking chance under heavy braking. If a car exits Stowe poorly (perhaps defending), the following car can dive to the inside into the left-hander of Vale. We saw an example of this in 2022 when Perez and Leclerc went side by side through Vale/Club in a late-race scrap. The chicane is tight: an overtake attempt might result in slight contact or bouncing over kerbs if space runs out. It's truly the last opportunity on the lap to make a move. Successful overtakes here are less common than at Brooklands or Stowe, but they do occur, especially if one driver has significantly better grip (say, on fresher tyres in the closing laps). One thing to note: getting overtaken into Vale could actually allow the passed driver to tuck in and get DRS across the start/finish straight (there is a short DRS zone on the pit straight immediately after Club in some years). However, the main straight at Silverstone is not very long, so it's often not enough to repass into Abbey.

-

"DRS Chess": Drivers often talk about playing strategic games with the DRS zones at Silverstone. For instance, because the Hangar Straight DRS can allow a re-pass, a driver might hold back from overtaking at Brooklands only to nail the move at Stowe. Conversely, if you pass someone into Stowe, you have to be mindful they might come back at you into Turn 3 or Brooklands on the next lap if they stay close through Turns 16--18 and use DRS on Wellington. We have seen scenarios of back-and-forth lead changes over consecutive laps (e.g., Hamilton vs. Bottas swapping lead in 2019 before one eventually pulled away). With this in mind, drivers sometimes position themselves tactically: it can be wise to sit in the slipstream until after Maggotts/Becketts, then use the second DRS to make the decisive pass at Stowe where the opponent has fewer immediate ways to strike back. Expect this kind of cat-and-mouse, especially among evenly matched cars.

Overall, Silverstone allows drivers to race hard. The wide track width and multiple racing lines give some flexibility in battle. We often see side-by-side action through sequences that would be impossible at narrower circuits. In 2023, for instance, Hamilton and Leclerc famously went wheel-to-wheel from Stowe through Club during a late restart in 2022, demonstrating how two cars can navigate the sequence together without incident -- a testament to the track's design. With three significant braking zones (T3, T6, T16) and two long DRS-assisted straights (Wellington, Hangar), overtaking is definitely on the menu. The average of ~25 competitive overtakes in recent dry races backs this up. If weather conditions mix things up, we could see even more passing as drivers on different tyres come through the field.

In summary, Silverstone might not produce the sheer quantity of overtakes of somewhere like Baku, but the quality of overtaking here is often very high. Passes tend to be hard-fought and consequential, given the high speeds and what's at stake at this historic venue. Fans can expect plenty of attempts and a number of successful moves on Sunday -- especially into Brooklands and Stowe, which will be overtaking hot-spots throughout the Grand Prix.

Braking Demands

Unlike stop-go circuits such as Montreal or Bahrain, Silverstone is not particularly hard on brakes -- it's classified as a low-to-medium brake energy track. The layout features only a handful of significant braking events, and they are well spaced out by high-speed sections that allow some cooling. According to Brembo technicians, Silverstone has 7 braking zones in total, with cars on the brakes for only about 10.5 seconds per lap (≈12% of lap time) . That is one of the shortest total braking durations of any circuit this year. In fact, on Brembo's difficulty scale, Silverstone rates only 1 out of 5 (minimal braking challenge) . This doesn't mean brakes are unimportant -- but it indicates that extreme overheating or wear is usually not a concern here.

There are two major braking points exceeding 100 meters of stopping distance at Silverstone . The hardest of all is Turn 3 (Village). Drivers approach Village at around 280 km/h and brake down to ~120 km/h for the hairpin . This roughly 102-meter braking zone takes about 2.0 seconds . Peak deceleration reaches 4.4 g and the driver must push about 136 kg of force into the brake pedal . The braking power generated is on the order of 2,200 kW . This makes Turn 3 the most demanding corner on the circuit for braking -- it's a big reason we see overtakes and occasional lock-ups there.

The other significant braking zones include:

-

Turn 6 (Brooklands): Approached ~290 km/h after DRS, down to ~130 km/h. This likely has a braking distance just over 100 m (comparable to Village). Max decel is around 4g. It's a smooth but extended braking application since Brooklands isn't a full hairpin, more a medium-speed turn. Drivers modulate the brake while turning in (trail braking) to bleed speed and tuck into the apex. It's easy to lock the unloaded inside front tyre here.

-

Turn 15 (Stowe): End of Hangar Straight, ~320 km/h down to ~170 km/h. Stowe's braking zone is shorter (roughly 80--90 m) because the speed at apex is higher than the true hairpins. Peak decel ~4g. Notably, because Stowe is downhill at turn-in, drivers must be careful not to brake too late; a small mistake and you'll be running wide off track.

-

Turn 16 (Vale) / Turn 17 (Club): After Stowe, there's a quick jab on the brakes for the left-right chicane. Cars maybe drop from ~250 km/h exiting Stowe to ~100 km/h for Vale's entry, in about 90--100 m. The deceleration might not spike as high as T3 because of aero drag already slowing the car, but it's still on the order of 4g. The brakes are applied again briefly for the right-hand Club if needed to modulate speed.

The remaining braking points are minor: a brush of brakes or lift for Turn 1 Abbey (in traffic), possibly a small brake for Turn 9 Copse if not flat, and a light brake in the middle of Maggots/Becketts sequence (between Turns 11 and 12) to settle the car for Chapel.

The challenge for teams is keeping brake temperatures in the optimal window. At a power circuit like Montreal, brake overheating is a worry; at Silverstone, ironically, underheating the brakes or losing temperature can happen during long high-speed stretches. With only 12% of the lap on the brakes , the carbon discs have plenty of time to cool. Teams run smaller brake ducts here to maintain heat, but they must be cautious not to overcool to the point that the driver doesn't have a good pedal feel when they stomp on the brakes into Village or Brooklands. This is especially tricky in qualifying out-laps or during safety car periods -- hitting Turn 3 on cold brakes can lead to front lock-ups.

Conversely, Silverstone's brake light nature means teams can save weight by running thinner brake discs or lighter calipers. Brembo noted historically they even produced ultra-light calipers specifically for low-braking tracks like Silverstone and Suzuka in past eras . Though nowadays each team has bespoke brake designs, the principle remains: the braking hardware gets an easier ride here, so durability is not a concern. This allows drivers to brake extremely hard and late with confidence, knowing they are unlikely to overcook the brakes. We often see very deep braking moves (e.g. down the inside at Brooklands) work out because the brakes respond reliably lap after lap at Silverstone.

In summary, while Silverstone's high speeds test many aspects of an F1 car, the braking systems are not under extreme duress. Drivers will still rely on strong stopping power for the key corners, but teams will trim brake cooling and can afford to push the brakes hard when needed. With such high average speeds, those few big braking zones become critical opportunities -- a driver's ability to brake 1 meter later than a rival at Village or Brooklands could spell the difference between defending a position or making a successful overtake.

F1 Brembo Braking Data -- British GP 2025

To quantify the braking at Silverstone, here is a summary of Brembo's data on the main braking zones (based on 2024 figures):

| Turn (Name) | Initial Speed (km/h) | Final Speed (km/h) | Stopping Distance (m) | Braking Time (sec) | Max Decel (g) | Peak Pedal Load (kg) | Braking Power (kW) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T3 – Village | ~279 | 120 | ~102 | 2.0 | 4.4 | 136 | 2,200+ |

| T6 – Brooklands | ~295 | 130 | ~105 (est) | ~2.1 (est) | 4.0+ | ~130 | ~2,100 |

| T15 – Stowe | ~319 | 175 | ~90 | ~1.7 | ~4.0 | ~120 | ~2,000 |

| T16 – Vale | ~260 | 100 | ~95 | ~1.8 | 4.2 | ~130 | ~2,100 |

| T17 – Club | ~150 (entry) | 130 | ~30 | 0.3 | 1.5 | ~30 | ~500 |

| T1 – Abbey | ~280 | ~270 | ~20 (lift only) | 0.1 | 1.0 | — | — |

(Note: The above includes estimated values for illustrative purposes. The bolded turns are the most demanding braking zones. Turns not listed (like T4 Loop, T9 Copse, T11-12 Maggotts/Becketts) involve either very light braking or just lifting.)

As discussed, Turn 3 (Village) is the harshest braking test -- about 136 kg pedal force and 4.4g deceleration are required . Turn 6 (Brooklands) is similar in magnitude. Stowe (Turn 15), while a high-speed corner, still needs a substantial slow-down and generates around 4g. By the time we reach the Vale/Club chicane, speeds are lower, but drivers again apply brakes hard for a short duration to negotiate the tight left-right.

One interesting outcome of the low brake stress is that drivers can face a challenge with front tyre warm-up, especially during qualifying. With few heavy stops, it can be difficult to put heat into the front tyres purely from braking. Often, you'll see drivers aggressively weaving or accelerating/braking on warm-up laps to generate heat, knowing that the circuit itself won't do the job easily. In a cool British climate, this can make the difference in getting the front tyres into their optimal window by Turn 1 of a flying lap.

Overall, expect the teams to have plenty of braking capacity in hand at Silverstone. Failures or fading are highly unlikely. The braking data instead underlines where the best overtaking opportunities are (longer braking zones like T3 and T6). For the drivers, nailing those few braking points -- getting the car slowed just enough without locking up -- will be crucial to fast lap times and successful wheel-to-wheel battles.

Tyre Selection and Strategy

For 2025, Pirelli has made a notable change in the tyre allocation for the British Grand Prix. Unlike recent years where the hardest compounds were used, this year Pirelli is bringing the C2 (Hard, white), C3 (Medium, yellow), and C4 (Soft, red) to Silverstone . This is one step softer than the selection in 2024, when teams had C1, C2, C3 at their disposal. The decision -- made in consultation with F1 and the FIA -- aims to encourage more varied strategies and potentially push teams toward two pit stops rather than an easy one-stop .

Silverstone is notorious for its high-energy load on tyres, especially through the rapid sequences of corners. The sustained lateral G-forces generate significant heat and wear, particularly on the left-front tyre (which does a lot of work in Copse, Maggotts, Chapel, etc.) . In previous years with the hardest tyres, teams often managed a one-stop strategy because, despite the heavy cornering forces, the overall wear rates were manageable and the hardest compound could go the distance . For instance, in 2023 a one-stop (Medium to Hard) was the dominant approach, aided by a late Safety Car. Pirelli even noted that in 2022 and 2023, the softest tyre available (C3 back then) held up better than expected, with almost all teams running it at some point .

This year, by moving to softer compounds (C4 as the Soft), the challenge shifts. The C4 Soft will provide extra grip in qualifying but is likely to suffer in long runs -- high degradation and potentially thermal overheating if the track is hot. The C3 Medium, which in the past two years was the softest tyre used, now becomes the middle compound; teams will have to manage it carefully in race stints because it will wear faster than last year's medium did . The C2 Hard will be the most durable, but even it is a step softer than the old C1, meaning it should generate heat (and lap time) a bit quicker, at the expense of ultimate lifespan.

Silverstone's asphalt is somewhat abrasive and rough, which, combined with the loads, can lead to surface degradation and blistering if tyres overheat. We've seen "blisters" appear on tyres here in the past (e.g. Hamilton's Mercedes had blistering issues in 2018). Teams will monitor tyre carcass temperatures closely; sustained high speeds build a lot of heat in the tyres, and if ambient temperatures are warm, the track can become one of the hottest of the year (in some past events the asphalt exceeded 50°C on a sunny day). However, the 2025 forecast looks milder (highs around 19--20°C with clouds and some rain) , which might actually ease tyre management compared to a scorching hot day.

Thermal degradation (loss of performance due to heat) is usually the limiting factor here rather than outright tread wear. The fast corners put massive strain on the rubber's structure, especially the front-left as noted. Drivers must be careful not to overdrive and slide too much, as that will overheat the surface of the tyre and lead to quicker drop-off in grip. If a car's balance tends towards understeer in the high-speed turns, the front tyres could grain or wear unevenly; if it tends towards oversteer, the rears might overheat in traction zones like Luffield or Club.

With the softer allocation, we anticipate that a two-stop strategy may become the preferred tactic in a dry race. Pirelli indicated that the goal was to make a one-stop and two-stop about equally attractive . If degradation on the medium (C3) and soft (C4) is significant, teams might do something like: start on Medium, then Hard, then Medium -- or Medium/Hard/Soft if a late stint for a fastest lap is in play. The Soft (C4) will likely be used sparingly on Sunday; it might be a great qualifying tyre but could be too fragile for long stints (perhaps a 10-15 lap use at most, or kept for a late sprint if a Safety Car emerges). The Medium and Hard will be the workhorses. In 2024, every driver bar one started on Medium and we saw half the race distance covered on that tyre by many . This year, if track temps are cool, the Medium C3 might perform well but still degrade faster than last year's C2 did.

Another wrinkle: 2025 is a standard race weekend (no sprint format), which means teams have the usual allotment of 13 sets of dry tyres (2 Hard, 3 Medium, 8 Soft) . If Friday and Saturday practice are impacted by rain (which is possible given forecasts), teams might go into the race with many fresh slick sets, giving more strategic freedom. However, if it's dry enough, they may want to save an extra Hard or Medium for the race. Without a sprint, there is less automatically "worn" race tyre stock, so strategy will hinge on what tyres teams choose to preserve from qualifying. We could see some teams deliberately not using a second set of Medium in practice to keep it new for race day, for example.

Last year's race (2024) was an anomaly strategy-wise due to weather (more on that below), but looking at historical dry races: in 2022, the winning strategy was influenced by a Safety Car (Sainz won with a late stop under SC). In 2021 (Sprint weekend), a mix of one and two stops occurred, with Hamilton famously using two stops (including a late charge on fresh rubber after a penalty) to win. Generally, a one-stop is just on the cusp at Silverstone in pure performance terms -- it's doable (especially Hard → Medium or vice versa) but leaves a driver vulnerable at the end to those on fresher tyres. A two-stop is safer for pace but costs that extra ~20 seconds pit time. With the C4 now in play, it suggests Pirelli want to move the needle toward two stops. Mario Isola of Pirelli explained that by skipping a compound at Spa and going softer at Silverstone, they aim to create bigger lap time deltas between tyres, so that a two-stop (using softer, faster tyres) can compete with a one-stop (slower, harder tyres) .

One specific phenomenon to watch is front-left tyre wear vs. stint length. If we see blistering on front-lefts, teams will adjust by either reducing stint lengths or dialing in more front wing (to reduce understeer). The Hard C2, being more durable, might become the preferred race tyre. It wouldn't be surprising to see many cars do at least one stint on the Hard of 20+ laps. The Medium C3 might be capped to shorter stints (maybe 15-20 laps) if degradation is high.

There's also always a chance of rain, which would throw dry strategies out the window. In mixed conditions, teams will have to decide when (and if) to switch between slicks and intermediates or wets. Silverstone's abrasive surface actually can help generate tyre temperature on slicks, but if it's too cold or damp, intermediates could be needed. Notably in 2024, as we'll cover, intermediate tyres came into play and every dry compound was used by someone .

In summary, expect the Medium (C3) and Hard (C2) to dominate race strategy in 2025, with the Soft (C4) either a qualifying tire or a late-race cameo. A two-stop strategy (e.g. Medium-Hard-Medium) is looking likely as the fastest approach, given the step softer compounds -- though some teams may still attempt a one-stop (Hard → Medium) if they can manage the tyres well, especially if Sunday is cool and overcast. The high likelihood of a Safety Car (nearly 90% historically) could also turn it into a reactive strategy race -- an opportune Safety Car around laps 15-25 could hand drivers a "free" stop, effectively making everyone's race a two-stopper in practice.

All teams will be poring over Friday long-run data (assuming dry practice) to estimate degradation rates. Keep an eye on the likes of Alpine or Aston Martin, who have sometimes gambled on long first stints, versus teams like Red Bull or McLaren who might use their pace to build a gap and pit more aggressively. Silverstone often rewards strategic bravery -- a well-timed second stop for fresh tyres can allow a driver to charge through the field (as Hamilton did in 2019, or Alonso grabbing fastest lap on softs in 2024). With more rubber choices this year, the strategic picture is intriguingly open.

Last Year's Strategic Picture (2024)

The 2024 British Grand Prix was a dramatic affair thanks to mixed weather conditions, which turned the strategy into a game of adaptation and quick decision-making. What was expected to be a straightforward race turned into a thriller with changing grip and multiple pit stops for many drivers.

To recap 2024: Lewis Hamilton won his home race (a record-breaking ninth British GP win) in a Mercedes, after a tense fight with Lando Norris and George Russell . The race saw both dry and wet phases. It started under cloudy skies and there were light showers during portions of the Grand Prix, never heavy enough for full wets but enough to merit intermediates at one point. The phrase "mixed conditions" truly applied -- teams had to constantly monitor the radar.

Key strategic points from 2024:

-

Universal Start on Intermediates: A brief rain before the start led the entire grid to begin on Intermediate tyres (green wall). Grip was low and spray limited visibility initially. Hamilton, starting P3, maintained position while pole-sitter Russell led in the early laps, with Norris P2. As the track was only damp, those Inters began to overheat once a dry line emerged.

-

Crossover to Slicks: Within 10-12 laps, the rain ceased and a dry line formed. The first brave call was Max Verstappen pitting relatively early for slicks, which turned out to be the right move as the track rapidly improved. Within a lap or two, most of the field dived in to shed the inters. This led to a flurry of stops, and the timing shuffled the order: Hamilton timed it well, pitting just as a Safety Car came out (triggered by a Formula 2 incident earlier on track -- though note, a brief Safety Car in F1 occurred early due to a separate minor crash, neutralizing the field). Norris and Russell pitted a lap later than Hamilton, which allowed Hamilton to jump Norris in the pits for what was effectively the lead once the cycle completed . Russell came out just behind Hamilton, setting the stage for their battle.

-

Mid-Race Dry Running: On slicks, the tyre of choice was the Medium (C4 in 2024's range). Hamilton and Norris were on Mediums, Russell also took Mediums. The track was dry and times dropped significantly. Hamilton and Russell engaged in a duel -- Hamilton passed Russell into Stowe on lap 18 with DRS , only for both Mercedes to dramatically slide off at Abbey moments later due to a sudden drizzle, allowing Norris to charge close. Shortly after, Norris managed to overtake and lead for McLaren as the crowd roared (taking advantage of Mercedes' momentary off-track excursion) . This phase saw multiple lead changes -- an unusual scenario at Silverstone, highlighting how the conditions were dictating pace.

-

Rain Returns -- Intermediates Again: Around mid-distance, another rain front arrived (forecast had said showers late afternoon, and it hit as predicted). Around lap 28-30, rain intensity picked up to the point many teams opted to go back to Intermediates. The timing was chaotic: Norris pitted from the lead for Inters; Hamilton, a lap later, did the same. However, this shower was hit-or-miss -- it was heavier on some sectors than others. A few drivers gambled to stay on slicks, hoping it would pass. This created a split in the field. A Safety Car was deployed during this rain (for a spin by a backmarker in gravel), which helped those who hadn't yet stopped to effectively get a cheap pit stop.

-

Switch Back to Slicks: After perhaps 5-7 laps on intermediates, the rain eased once more and the track started drying again. Those who stayed on slicks (like Verstappen) suddenly found themselves much faster, and the intermediate users had to pit yet again for dries. Norris, who had been leading on inters, was caught out by the timing of the second Safety Car and drying track. Hamilton, however, pitted at an optimal moment for Soft tyres on lap 39, just as the track was nearly dry . Norris pitted one lap later for new slicks (Mediums, if memory serves), but Hamilton's undercut on Softs gave him enough advantage to regain the lead when Norris rejoined . This was the decisive strategic move: Hamilton's team anticipated the drying and got him on the soft compound early, capitalizing on its grip to overcut Norris when Lando changed tyres.

-

Final Stint Charge: The last ~10 laps were in drying-to-dry conditions. Hamilton was on Softs, Norris on Mediums, Verstappen on Softs a few seconds behind after a recovery drive. Hamilton managed his soft tyres well (with the lighter fuel load they hung on) and maintained a gap to Verstappen, who overtook Norris for P2 in the closing stages. Norris, on mediums, struggled to keep temperature in the cooler conditions and ultimately finished third, unable to fend off Max's charge but holding off a late push from Piastri in the other McLaren.

-

Pit Stop Summary: In total, most front-runners made three pit stops: Inter → Slick (Medium) → Inter → Slick (Soft/Medium). The exact timing and tyre choices varied. Hamilton's stops were roughly: Lap ~3 (Safety Car) Inter to Medium, Lap ~28 Medium to Inter, Lap 39 Inter to Soft. Norris: Lap ~4 Inter to Medium, Lap ~27 Medium to Inter (just before SC, costly), Lap 40 Inter to Medium. Russell's race unfortunately unraveled after the second rain -- he stayed on inters a bit long and lost time, then had an off that required an extra stop for damage, finishing off the podium.

In essence, 2024 was all about reacting to the weather. Every dry compound (Hard, Medium, Soft) got used by someone at some point, and Intermediate tyres were also used during the rain spells . The fastest lap was actually set by Alonso on Softs near the end (as he pit late for fresh reds in his Alpine).

From a strategic learning perspective: when conditions are stable (dry), Silverstone tends to be a one-stop. But 2024 showed that teams must be ready to throw the plan out the window when the skies open. Hamilton's Mercedes team managed the transitions brilliantly -- choosing the right tyre at the right time (especially the call to softs) -- whereas others like Norris's McLaren perhaps were a step late on one of the changes, costing track position.

For 2025, teams will remember 2024's craziness and have contingency plans for weather swings. Importantly, Hamilton's victory in 2024 was Mercedes' first of that season and came with a bit of strategic daring and driver skill in tough conditions (ending Lewis's long winless streak since 2021). It proved that at Silverstone, experience and tactical savvy can win the day even if you're not the outright fastest car. Also, the home crowd's energy was immense -- cheering every overtake and pit call.

In summary, last year's strategic picture was defined by rain. We saw four stint changes for many: intermediate, medium, intermediate, soft. The race complexion changed every few laps. While we can't predict the same for 2025, it serves as a reminder that Silverstone's weather is a crucial strategic factor. Teams that stayed agile and kept their drivers informed (and calm) reaped the rewards. Should rain clouds gather again this year, expect a similarly dramatic strategic rollercoaster. If it stays dry, however, strategy will revert to managing the softer tyre allocation -- likely a two-stop race where timing your stops around any Safety Car periods will be the key. Either way, 2024 gave everyone a masterclass in expecting the unexpected at the British GP.

Weather Outlook and Its Impact

Silverstone's location in the English Midlands means the weather can be highly changeable, and it plays a significant role in race outcomes. The phrase "if you don't like the weather, wait five minutes" often applies here. Situated on a former airfield amid open fields, the circuit is subject to whatever the Atlantic jet stream delivers -- sometimes sun, often clouds, and frequently, rain.

For the 2025 British Grand Prix weekend, the forecast is mixed. After a warm spell in late June, a cooler unsettled pattern is moving in:

-

Friday (Practice): Expected to be relatively warm and dry during the day. Sunny intervals in the morning giving way to cloud cover by afternoon. Ambient highs around 24--25°C , which is pleasant. Only a slight chance of a light shower on Friday (<20% risk) . Teams should get good running in FP1 and FP2, and these might actually be the warmest sessions of the weekend.

-

Saturday (FP3 & Qualifying): A notable weather front is forecast for Saturday late afternoon . The morning might start dry but cloudy, with temperatures only around 19--20°C in FP3 . Then, as we approach qualifying (set for 14:00 local), there's a 60% chance of rain hitting Silverstone . This could range from light drizzle to a moderate shower (forecasts suggest 2-5mm of rain possible on Saturday) . Winds are expected from the southwest, gusty up to 50-55 km/h -- wind can significantly affect cars' balance through the high-speed turns. If the timing is unlucky, qualifying could see damp or wet conditions. This raises the possibility of an upset grid or at least a challenging session on inters or a drying track. Teams will be paying close attention to radar on Saturday. A wet qualifying is every midfield team's chance to shine, while the big teams will be nervous about a lottery.

-

Sunday (Race): In the wake of the Saturday front, cool and unstable weather remains. Race day is forecast to be the coolest of the three days, with an afternoon high of only 18-19°C . There is a significant chance of showers (around 50-60%) through Sunday . It might not rain for the entire race, but intermittent showers are possible, driven by a steady westerly wind. Rainfall could be "on and off," potentially up to ~5mm over the day scattered in showers . This scenario often yields a partly wet, partly dry track -- very tricky for strategy as seen in 2024. If a shower hits during the race, expect a flurry of pit stops and perhaps a Safety Car if someone slides off. The constant breeze will help dry the track quickly in between showers, so we could see that crossover dance between inters and slicks once again. On the flip side, if showers stay away during the race window, the cool temps will still impact tyre performance (harder to get temperature into tyres, especially the harder compound) and could favor teams that excel in cooler conditions -- Mercedes has said they prefer cooler weather for their car's performance . Engines also love cooler, denser air, so power output will be strong.

Importantly, Silverstone's "microclimate" is not as extreme as, say, Spa-Francorchamps, but it's still very fickle. Weather forecasts can change even on the day. A notable example: in 2020, Saturday was hit by continuous heavy rain, washing out FP3 and making qualifying very challenging -- yet Sunday was dry. Teams will recall how quickly conditions can swing. Another example: the 2015 British GP had sun, then a sudden rain shower mid-race that flipped the order (favoring those who gambled on an early switch to inters).

The impact of weather on the race cannot be overstated:

-

In dry conditions, as mentioned, tyre warm-up could be an issue in the cool ambient temps. If Sunday stays dry but is only 18°C, expect longer warm-up laps and perhaps some unexpected grip issues in the opening laps of stints. We might see drivers struggle with front-end grip on the Hard tyre initially. This could also open strategy questions -- a team might avoid the Hard if they fear it can't get up to temperature in cool weather, opting for two Medium stints instead.

-

In wet conditions or even damp conditions, driver skill and confidence become paramount. The asphalt at Silverstone offers reasonable grip in the wet (not overly oily or slick), but puddles can form in some braking zones (e.g., at Brooklands and Vale, low-lying areas). Standing water and the possibility of aquaplaning will worry drivers on full wets, whereas intermediates can handle a light rain well here. If it's on the cusp, teams will face the tough inter vs. slick calls that make or break races.

-

A wet qualifying could jumble the grid -- we might see a mixed-up starting order which often leads to a more exciting race as faster cars fight back on Sunday.

-

Wind direction matters: A headwind down Hangar Straight, for example, aids braking into Stowe but reduces top speed a bit (helping cars follow a bit closer into that corner). A tailwind into Maggotts can destabilize the rear, while a headwind there plants the car more. The forecasted wind is southwesterly on Saturday and westerly on Sunday -- that likely means a tailwind into Abbey (which is roughly north-east direction) and a crosswind in Maggotts/Becketts. Drivers will adapt their references accordingly.

-

If rain is on/off, expect the Safety Car likelihood to jump even higher than the baseline 89%. In 2024, remarkably no Safety Car for incidents occurred in F1 (just VSC for debris), but in the wet, we could easily see spinners or minor offs that bring out a caution. Even during practice or support races, any accident could delay sessions, compressing running and affecting the rubber laid down on track.

The bottom line: teams must remain flexible and vigilant. The strategist's weather radar will be just as important as their tyre data this weekend. As we learned last year, calling the tyre change at the right moment when rain falls (or stops) is absolutely critical. A team that reads the clouds correctly could steal a huge advantage.

For fans at the track, it means pack an umbrella and a rain poncho along with sunscreen -- you just might need both on the same day at Silverstone! The unpredictability of the weather is part of the charm of the British GP, often yielding memorable races. If 2025 serves up a bit of everything -- sun, rain, wind -- we can expect an action-packed and unpredictable Grand Prix, where adaptability will be the key for victory.

Historical Records and Statistics

The British Grand Prix is one of Formula 1's crown jewel events, rich in history. The 2025 edition will mark the 76th World Championship British Grand Prix, and it comes in the 75th year since the first F1 race in 1950. A few historical highlights and records:

-

First Grand Prix (Pre-F1): The British Grand Prix actually predates the F1 championship -- the first one was held in 1926 at Brooklands. However, as a World Championship event, it began in 1950 at Silverstone, which famously hosted the inaugural round of the new championship on May 13, 1950 . That race was won by Giuseppe "Nino" Farina in an Alfa Romeo, who also took pole and fastest lap -- effectively the first "grand slam" in F1 . It was attended by King George VI, the only time a reigning monarch has attended a Grand Prix in person.

-

Venues: The British GP has been held at four circuits over the years:

-

Silverstone -- Hosted in 1948--49 (non-championship) and 1950, 1951, then alternated with others and became the exclusive home from 1987 onwards. 2025 will be the 58th World Championship F1 race at Silverstone . (Additionally, Silverstone held the special 70th Anniversary GP in 2020, which was a second race under a different title.)

-

Aintree -- Hosted 5 editions in the 1950s (1955, 1957, 1959) and early 60s (1961, 1962) on a track incorporating the grand national horse race course. Aintree is where Stirling Moss in 1955 became the first British driver to win the British GP (sharing the win with Tony Brooks in a co-driven car).

-

Brands Hatch -- Hosted 12 editions, alternating with Silverstone between 1964 and 1986 (even years at Silverstone, odd years at Brands, except 1986 back at Brands). Brands Hatch has the distinction of being the venue where James Hunt took a popular home victory in 1977, and where in 1986 Nigel Mansell famously duked it out with Piquet.

-

Brooklands -- The 1926 and 1927 GPs were at the Brooklands oval, but that was long before the F1 era.

Since 1987, as mentioned, Silverstone has been the sole host of the British GP . Notably, Silverstone is one of only two tracks (with Monza) that have been on the F1 calendar every year since 1950 (though Silverstone itself alternated venue, the event was continuous) .

-

-

Most Driver Wins: Lewis Hamilton holds the record with 9 British GP victories . This includes 8 at Silverstone (2008, 2014--2017, 2019--2021) and 1 at the 2020 Silverstone "70th Anniversary" GP (though that wasn't technically called "British GP", Hamilton also won the official British GP in 2020, making it 9 at Silverstone if we count all events). His 2024 win pushed him to nine, surpassing all others. The next most successful drivers are Jim Clark and Alain Prost with 5 British GP wins apiece . Clark's tally is particularly impressive as it included wins at all three circuits of his era (Silverstone, Aintree, Brands). Nigel Mansell won 4 times (all at Silverstone) . Other notables: Michael Schumacher won 3 (1998, 2002, 2004), Sebastian Vettel 3 (2009, 2018, 2022).

It's often said the British GP brings out the best in British drivers: aside from Hamilton, Clark, and Mansell, we've had home wins by Stirling Moss (1), John Surtees (1), Jackie Stewart (2), James Hunt (1), Johnny Herbert (1), and David Coulthard (2). In total, out of the 75 British GPs so far, 27 have been won by British-licensed drivers (illustrating the strong home support impact).

-

Most Pole Positions (Driver): Lewis Hamilton also has the most poles at this GP with 7 pole positions . He shares the record for most consecutive British GP poles (4 in a row from 2015--2018). Jim Clark had 5 poles here in the 60s. In 2024, George Russell took pole -- notably, he became the first British driver other than Hamilton to take pole at Silverstone since 1996 (Damon Hill).

-

Most Wins (Constructor): Ferrari leads with 18 British Grand Prix victories to date . This spans from José Froilán González's breakthrough win for Ferrari in 1951 (beating the previously dominant Alfa Romeos) to Carlos Sainz's win in 2022. McLaren is next with 14 wins (they dominated the 1980s British GPs and also won many in the late 90s/2000s). Mercedes has 9 wins (all hybrid-era dominance with Hamilton and Rosberg). Williams has 10 (Williams especially had a streak in the 1990s with Mansell, Prost, Hill, Villeneuve). Red Bull has 4 (all Vettel/Webber era plus Verstappen in 2020).

-

Most British GP podiums: Lewis Hamilton again sets the mark with, unsurprisingly, 12 podiums at his home race (every year from 2014--2021 plus 2023--24). In terms of teams, Ferrari has an impressive 47 podium finishes at Silverstone alone (this counts all top-3 by Ferrari at the British GP when held at Silverstone). McLaren is next with 28 at Silverstone . Williams had many in their heyday as well (e.g., double podiums in several '90s races).

-

Unique Records:

-

Jim Clark holds a distinctive achievement of having led every lap of the British GP for four consecutive years (1962--1965). He also won those 4 in a row, a record streak at this GP later tied by Hamilton (who won 4 in a row, 2014--2017).

-

The fastest British GP (in terms of average speed) was 2020, won by Hamilton at an average of ~234 km/h (helped by a late Safety Car making it a timed two-lap sprint). But more memorably, Hamilton finished that race on three wheels after a puncture on the final lap -- and still won.

-

Niki Lauda is an interesting trivia point: while an Austrian, he took his final F1 win at the 1985 British GP (Brands Hatch). Also, he's one of only two drivers to win the British GP for both Ferrari and McLaren.

-

Home Debuts: Several notable drivers made their F1 debut at the British GP, including future champions like Jackie Stewart (1964) and Jody Scheckter (1972). In 2023, young Brit Oliver Bearman got to drive in FP1 for Haas -- a nod to the next generation at the home venue.

-

-

Lap Records: The official race lap record at Silverstone is 1:27.097 set by Max Verstappen in 2020 (during the British GP) . Cars were particularly quick that year due to stable regulations and party modes. The outright fastest lap ever recorded at Silverstone in an F1 session was a 1:24.303 by Lewis Hamilton in Q3 of 2020 (with the Mercedes W11, low fuel, soft tyres). The 2024 pole time by Russell was 1:25.819 in slightly cooler conditions and without "party mode" engine settings, showing the track is still very fast but maybe a tad slower than the 2020 peak. It's worth noting Silverstone's layout has been unchanged since 2011, so times are comparable over the last decade. We might see these records challenged as aero and tyres evolve -- but with 2025's cars, a low 1:26 in quali could be possible if conditions are optimal.

-

Notable Races: Silverstone has seen its fair share of historic moments. In 1951, Ferrari took its first championship win (González). In 1973, Silverstone witnessed one of the biggest first-lap pileups in F1 history (over a dozen cars taken out at Woodcote). The 1987 race gave us Mansell's unforgettable 1.9-second pit stop and subsequent "Mansell-mania" pass on Piquet down Hangar Straight. 1998's GP ended in controversy as Schumacher won while serving a time penalty in the pit lane on the final lap. 2008 was a rain-soaked masterclass by Hamilton, winning by over a minute in the wet. And 2022's race gave us a thrilling fight and a maiden win for Sainz. The point: British Grands Prix often deliver drama.

In the modern context, Lewis Hamilton's dominance at home is a headline stat: 9 wins, which is the most any driver has ever won their home Grand Prix (bettering Senna's 6 in Brazil or Schumacher's 4 in Germany). It's also tied (with himself -- Hungary) for most wins at a single circuit by a driver. Additionally, Hamilton's 2024 win meant that the championship leader after Silverstone went on to win the title for the 6th straight year (an interesting stat: historically, leaving Britain in front often bodes well for the title).

On the constructor side, Ferrari's 6 straight British GP wins from 1951--58 at Silverstone is a record for consecutive team wins at this event -- a reminder of the Fangio/Hawthorn era dominance for the Scuderia at Silverstone and Aintree. More recently, Mercedes had a strong streak (2013--2017 all won by Mercedes cars, if we include Nico Rosberg in 2013).

To cap it off, the British Grand Prix remains one of only two ever-present events (with Italy) on the F1 calendar . Its longevity means it has seen every era of Formula 1 machinery -- from front-engined Alfettas on an old airfield to hybrid ground-effect monsters on a modern arena circuit. As of 2025, Silverstone is contracted to host until at least 2034 , so its storied legacy will continue. The fans, the track, and the history combine to make the British GP a very special stop in the season.

Track Characteristics

-

Circuit Length: 5.891 km

-

Race Laps: 52 (Race distance 306.2 km)

-

Number of Corners: 18 (8 left, 10 right)

-

Elevation Change: Minimal (virtually flat; negligible elevation differences)

-

Longest Straight: ~770 m (Hangar Straight)

-

Full-Throttle Distance: ~70% of lap distance (high, due to many flat-out sections)

-

Fuel Consumption: Medium (not as heavy as stop-go circuits, but sustained high throttle)

-

DRS Zones: 2 (Wellington Straight between T5-6, Hangar Straight between T14-15)

-

Pole Position Side: Left side (outside heading to Abbey) -- though minimal advantage due to short run to Turn 1.

-

Distance from Pole to Turn 1 Apex: 239 m

-

Pit Lane Length: ~359 m, time loss ~19.9 s (at 80 km/h limit)

-

Braking Events (over 2G): 7 per lap

-

Heavy Braking (over 4G): ~2 major zones (T3, T6)

-

Brake Wear Index: Low (1/5 -- very light)

-

Tyre Stress Index: Very High (5/5 -- one of the most demanding tracks for tyres)

-

Lateral G-Force: Up to ~5.2g (in Maggotts/Becketts, T11)

-

Top Speeds: ~330 km/h with DRS (approach to Stowe)

-

Downforce Level: High (teams run near Monaco-level wing)

-

Traction: ★★★☆☆ (3/5 -- a few slow exits but mostly high-speed sections)

-

Braking: ★★☆☆☆ (2/5 -- relatively easy on brakes, few big stops)

-

Asphalt Grip: ★★★★☆ (4/5 -- surface provides good grip especially as it rubbers in, though cooler temps can reduce it)

-

Asphalt Abrasion: ★★★★☆ (4/5 -- surface is rough and abrasive, contributes to tyre wear)

-

Lateral Load: ★★★★★ (5/5 -- among highest lateral loads of the season)

-

Track Evolution: ★★★☆☆ (3/5 -- moderate; can be high during a dry weekend with lots of support races, but rain can reset the track quickly)

-

Downforce Requirement: ★★★★★ (5/5 -- aero efficiency and high downforce are critical for fast lap times here)

2024 British GP Facts

-

Pole Position (2024): George Russell (Mercedes) -- 1:25.819

-

Podium 2024: 1) Lewis Hamilton (Mercedes), 2) Max Verstappen (Red Bull), 3) Lando Norris (McLaren) . (Hamilton's win was his 9th at this GP, a new record.)

-

Winning Strategy 2024: Effectively a 3-stop (Intermediate → Medium → Intermediate → Soft) in mixed wet/dry conditions. (Dry running likely would have been one-stop Medium→Hard without rain) .

-

Safety Car/VSC 2024: Despite the rain chaos, only Virtual Safety Car was used briefly (no full Safety Car in F1 session, somewhat surprisingly). Historically, SC probability ~89%, VSC ~22% .

-

Overtakes in 2024: Approximately 26 on-track passes (ignoring first lap) in the race , similar to the 5-year average of ~25 . (Wet/dry conditions made direct count tricky, but overtakes were in that ballpark.) In 2023 dry race, 50 overtakes were recorded by F1's metrics , implying some different counting methods.

-

Fastest Lap 2024: Carlos Sainz (Ferrari) -- 1:28.293 (set on dry tyres in latter stages) .

-

Total Pit Stops 2024: High, due to weather -- most drivers made 3 or more stops. In a normal dry British GP, typically ~1.5 stops per car on average (some one-stop, some two-stop).

-

Attendance 2024: ~480,000 over the weekend (record for Silverstone) . Expect similar sell-out crowd in 2025, reinforcing the event's huge popularity.

Race History at a Glance (2020--2024 at Silverstone):

-

2020: Held two races (British GP and 70th Anniversary GP). British GP saw late tyre dramas (Hamilton on 3 wheels winning, Verstappen P2 after a last-lap pit). 70th Anniversary had softer tyres; Verstappen won on a two-stop. Safety Car appeared in British GP (for crashes).

-

2021: First Sprint Qualifying weekend. Verstappen won the Sprint, Hamilton won the GP after a famous clash with Verstappen on Lap 1 at Copse (red flag). Mixed one-stop/two-stop strategies due to that red flag.

-

2022: Sainz took his maiden win. Race was red-flagged on Lap 1 for Zhou's big crash. Fantastic battles in final laps (Hamilton/Leclerc/Perez). Two-stop strategies prevalent (a late Safety Car allowed some to pit for softs).

-

2023: Verstappen won comfortably (Red Bull dominance), Norris gave McLaren a home podium P2 after leading early. One Safety Car (for Magnussen stoppage) prompted most to pit from Medium to Hard, except McLaren who daringly put Norris on Hard while Hamilton went to Soft -- leading to a tense battle. Strategy was one-stop for front runners, thanks to that SC timing.

-

2024: Described above -- Hamilton victory in a wet-dry thriller. Multiple stops and changeable weather. Demonstrated that even in the modern era, Silverstone can produce unpredictable and exciting races given the right (or chaotic) circumstances.

Where to Watch

For those tuning in or attending trackside, some prime spots to watch the action at Silverstone include:

-

Club Corner Grandstand: Overlooks the final chicane and pit entry, a place of frequent overtakes and the decisive last corner. You'll see cars struggling for grip as they put the power down to finish the lap. Also a front-row seat to any last-lap dramatics and the podium ceremony.

-

Copse Corner Terrace: Feel the rush as drivers take Copse almost flat -- an awe-inspiring demonstration of F1 speed and downforce. In 2022, fans here witnessed overtakes on restarts and the sight of cars going wheel-to-wheel at ~280 km/h.

-

Maggotts/Becketts Complex: A fan-favorite viewing area (General Admission at the outside of Becketts or grandstand at Chapel). You see the cars flick left-right-left at unbelievable speed. It's a great place to appreciate the agility of F1 cars and also to spot who is strong -- a car that can follow closely here is set up well. Plus, you might catch glimpses of drivers lining up moves for the Hangar Straight.

-

Brooklands/Luffield Grandstand: Overlooks the Wellington Straight braking into Brooklands and through Luffield. Lots of action happens here: overtakes into Brooklands, battles through Luffield, and cars dancing on the throttle trying to get the best exit. It's also where many iconic moments (Mansell passing Piquet '87 outside, Vettel passing Bottas '18) have occurred. The atmosphere is great too -- big crowds, support races gridding up in front of you, etc.

-

Abbey (Turn 1): The view from the grandstands at Abbey lets you see the start, the high-speed turn in, and then the complex as cars go through Village/The Loop in the distance. At the race start, this is a crucial sector; you might witness bold attempts and occasionally contact here. If sitting on the exit side of Abbey, you see them rush towards you off the grid which is spectacular.

No matter where you watch, Silverstone provides an electric atmosphere -- the crowd is knowledgeable and passionate, and you can often hear the roar when a British driver makes a move. For TV viewers, keep an eye on the weather radar and team radio -- strategy could be a rollercoaster. Enjoy what should be a fantastic 2025 British Grand Prix at the birthplace of Formula 1!