Mercedes and Red Bull under fire: how F1’s 2026 power units rules could redraw the grid

The 2026 Formula 1 power unit era is already sparking controversy, with Mercedes and Red Bull under scrutiny over compression ratio tricks and looming battles on fuel energy flow that could redefine the competitive order.

2026 rules: why engines are under the spotlight

From 2026, F1 will keep the 1.6-litre V6 turbo but radically reshuffle how that power is delivered and controlled. The internal combustion engine (ICE) will contribute less of the total output, while the hybrid system – centered on a much more powerful MGU-K – becomes a decisive performance pillar.

At the same time, fuel flow will no longer be limited by mass (kg/h) but by energy flow, a subtle but fundamental shift that turns sustainable fuels and chemical ingenuity into a performance battlefield. This happens alongside stricter prescriptions on ICE geometry and turbo layout, reducing design freedom while pushing teams to squeeze every legal advantage from combustion and energy management.

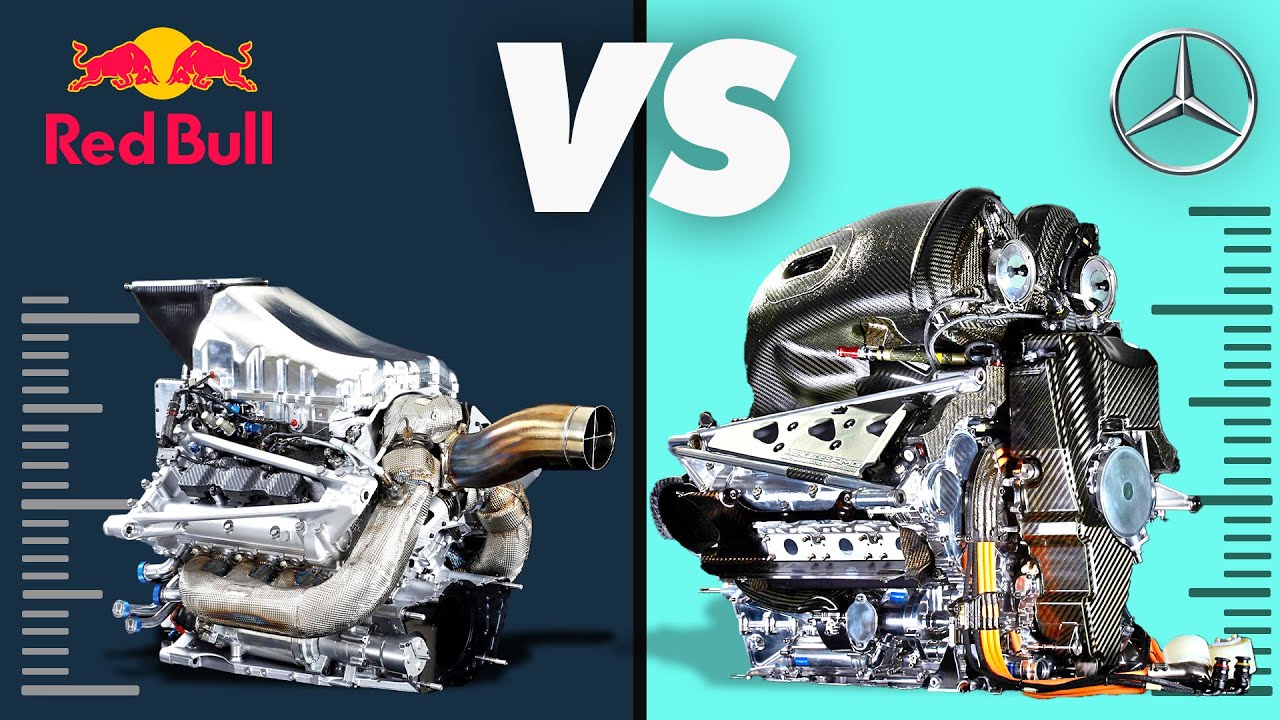

Compression ratio controversy: Mercedes and Red Bull in the crosshairs

The first flashpoint of the 2026 era is the accusation that Mercedes and Red Bull Powertrains may have found a way to increase the effective compression ratio beyond the new 16.0:1 limit. Until 2025, regulations tolerated compression ratios around 18.0:1, but the 2026 rules have reduced that maximum, ostensibly to balance performance and reliability with new fuels and hybrid targets.

Rival manufacturers – named in the Italian press as Ferrari, Audi and Honda – have asked the FIA for clarification, fearing that temperature-dependent geometry changes could push the ratio back up towards 18.0:1 in running conditions while remaining legal in static scrutineering at ambient temperature. The suspicion centers on the use of materials that expand differently when hot, slightly altering combustion chamber volume and thus effectively increasing compression at operating temperature.

In simple terms, compression ratio expresses how many times the air–fuel mixture is compressed between bottom dead centre and top dead centre inside the cylinder. Higher compression improves thermal efficiency and therefore power and fuel economy, but it also increases the risk of knock and uncontrolled combustion, which can be fatal for reliability if the fuel and combustion strategy are not perfectly matched.

FIA position and the “flexi engine” analogy

The FIA has responded by stressing that the regulations clearly define the maximum compression ratio and the method for measuring it, which is based on static conditions at ambient temperature. The governing body acknowledges that thermal expansion can influence dimensions but notes that the current rules do not allow measurements at elevated temperatures, effectively creating a potential grey area.

Internally, the situation has already been compared to the saga of flexible wings, where components passed static tests but deformed under load on track in a way that delivered a performance benefit. In this engine case, any geometric variation would occur only at running temperature, which makes detection and enforcement more complex and raises questions about whether new test procedures or revised wording will be needed to ensure cars are compliant “at all times during the event”, as Article 1.5 conceptually requires.

The FIA has confirmed that the topic is on the table in technical forums with all power unit manufacturers and that further clarifications or even regulatory changes are possible if needed to guarantee fairness and clarity. That means teams working on the edge of the rules face the risk that clever interpretations may be curtailed before or during the first seasons of the new formula.

From kg/h to MJ/h: why fuel energy flow changes everything

Parallel to the compression debate, 2026 brings a less visible but arguably more impactful revolution: how fuel usage is measured and limited. Up to 2025, F1 controlled consumption via a fuel flow meter capped at 100 kg/h, alongside a maximum fuel load over the race distance.

From 2026, the key metric shifts to energy flow in megajoules per hour (MJ/h), with a formula that ties permitted energy to engine speed and imposes a maximum of 3000 MJ/h at high revs. Each fuel supplier must have its product characterized by an independent body, which will certify the energy content per unit mass (lower heating value), and that calibration then feeds into the control system that enforces the energy flow limit.

Ferrari engine technical director Enrico Gualtieri has explained that the sensor will effectively measure the energy flow, not just the raw fuel mass, and that each manufacturer will therefore run with a specific energy “signature” tied to its approved fuel. The total energy available per unit of time will be the same in regulatory terms, but a fuel with higher energy density allows the team to carry less fuel mass for the same energy budget, reducing weight and potentially offering a significant lap-time gain.

Synthetic fuels and the new development war

Because 2026 regulations require carbon-neutral or very low-carbon fuels, synthetic e-fuels become a central performance and image battleground. The rulebook intentionally leaves room for research on fuel chemistry, giving suppliers scope to develop new molecules and additives that control knock, improve combustion stability and protect reliability at high compression and high specific output.

Where conventional petrol fuels relied on a well-known family of anti-knock additives, future e-fuels will invite chemists to experiment with novel compounds that work within the FIA’s sustainability and safety framework. An “involuntary” underestimation of a fuel’s energy content in the laboratory could translate into a real on-track performance advantage if the engine is effectively consuming more energy than the certified value suggests, making calibration accuracy another politically sensitive issue.

For manufacturers, the upside is obvious: if F1 can demonstrate that efficient, high-performance combustion on synthetic fuels is possible at the pinnacle of motorsport, the technology and know-how gained can feed back into the wider automotive industry. That narrative is strategically important for brands like Audi, Honda, Mercedes and Red Bull’s partners as they balance combustion heritage with road-map commitments to decarbonization.

Mercedes and Red Bull: where might the advantage lie?

Mercedes and Red Bull Powertrains are already being portrayed as the early aggressors in exploiting 2026’s grey areas, starting with compression ratio management. Both operations have invested heavily in advanced simulation, materials science and combustion research, making them well placed to integrate clever thermal expansion strategies with fuel and ignition mapping if the rules allow it.

If a team can run an effective compression ratio close to 18.0:1 at operating temperature while staying within the 16.0:1 ambient test limit, it could unlock a meaningful efficiency boost that translates into more power for the same energy flow. Combined with a highly optimized MGU-K deployment strategy – remembering the 2026 MGU-K will be capable of around 350 kW with much higher allowed recovery per lap – that advantage could be magnified on circuits where energy deployment patterns are critical.

On the fuel side, Red Bull’s broader ecosystem links to companies involved in synthetic fuel development, while Mercedes’ long-standing ties with major fuel suppliers and its Brixworth engine base provide depth in chemical and combustion engineering. If either camp can secure a fuel that is both energy-dense and knock-resistant at high compression, they might start the 2026 cycle with a meaningful edge before convergence kicks in.

Ferrari, Audi, Honda: challengers and watchdogs

The response from Ferrari, Audi and Honda – moving quickly to seek FIA clarification – shows how sensitive the paddock already is to any perceived loophole. These manufacturers know that entering a new regulatory era even slightly on the back foot in combustion or fuel technology can lock in a disadvantage for several seasons, given homologation and cost-control constraints.

Ferrari has publicly highlighted the importance of accurate fuel characterization and has a long history of close collaboration with fuel partners on combustion research. Audi arrives with a strong corporate emphasis on sustainable fuels and electrification, while Honda has demonstrated in the current era that it can accelerate power unit development dramatically once the right architecture and organizational setup are in place.

Politically, these brands also have an interest in ensuring that no single competitor shapes the early interpretation of the rules to its sole benefit. That is why the compression ratio discussion is unlikely to remain just a technical debate: it may well become a test case for how tightly the FIA intends to police energy flow, geometry and materials innovation as the new formula begins.

What it means for racing

On track, the combination of higher electric power, tightly controlled energy flow and aggressive compression ratios will likely produce cars that are lighter on fuel but extremely sensitive to deployment strategy and thermal management. Drivers and engineers will juggle not just tyre life and battery state-of-charge, but also how to keep combustion in its optimal window as the fuel load reduces and the engine sees varying temperatures and pressures over a race stint.

For informed fans, these nuances will create a rich new layer of performance analysis: understanding why one team can sustain higher deployment on the straights, or why another seems to struggle with knock-induced performance clipping or reliability under certain conditions. This is exactly the kind of technical-political intersection that lends itself to deeper breakdowns, lap-time modelling and telemetry-based insight.