The 2026 Formula 1 season represents one of the most significant technical reset points in modern motorsport history. While much of the public discourse has focused on the revolutionary shift toward a 50/50 power split between internal combustion and electrical energy, or the introduction of active aerodynamics, a more fundamental factor is emerging as the true "great leveler." It is increasingly clear that success in this new era will hinge on a factor that has largely faded from relevance in recent campaigns: reliability.

With all-new chassis regulations, hybrid power units entering a fundamentally different phase of evolution, and a technical landscape that rewards efficiency over raw, unbridled power, teams face unprecedented challenges in delivering dependable machinery from day one. This convergence of factors is poised to make mechanical integrity the primary differentiator—a variable that could dramatically reshape the competitive pecking order and potentially end the era of predictable dominance.

Over the past five seasons, reliability has become almost a non-issue in Formula 1. The consistency and durability of contemporary hybrid power units and chassis have reached such a mature state that mechanical failures are rare. Retirements, when they occur, typically stem from aerodynamic damage, driver error, or strategic miscalculation rather than fundamental component failure. This stability has allowed the championship battle to focus almost exclusively on speed, strategy, and driver performance.

However, 2026 will fundamentally alter this dynamic. The introduction of all-new regulations presents an entirely different scenario. Teams are developing revolutionary power units with increased electrical power, new internal combustion engine configurations, and regenerative systems optimized for a different energy recovery philosophy. Simultaneously, the 2026 chassis regulations introduce aerodynamic philosophies and structural concepts that have been largely theoretical until testing begins in earnest. This convergence creates an environment where reliability concerns will resurface as a legitimate competitive factor for the first time in over a decade.

Scuderia Ferrari has been among the first teams to publicly acknowledge this reality. Team principal Fred Vasseur recently outlined a deliberately cautious approach to the 2026 season launch, signaling a shift in philosophy that prioritizes durability over early-season performance peaks. Rather than attempting to maximize every ounce of downforce or horsepower from the outset, Ferrari will debut with a basic "spec A" version of its 2026 car during a planned revelation on January 23, likely at the Fiorano test track.

Vasseur's reasoning is particularly instructive for understanding why reliability has suddenly become paramount. "The first target in this kind of season is to get the reliability," he stated, emphasizing that the team's priority for the initial testing phases will center on accumulating mileage to understand the car's dependability rather than chasing lap time differentials. This represents a fundamental shift in pre-season testing philosophy—a recognition that early-season DNFs (Did Not Finish retirements) could create a points deficit so substantial that teams may never recover their championship position, regardless of how fast they become by mid-season.

One factor that distinguishes 2026 from recent seasons is the expanded pre-season testing program. F1 teams will have access to nine cumulative test days before the Australian Grand Prix—a significant increase from the three days that characterized recent campaigns. This allocation consists of three days during the Barcelona test (held between January 26-30), followed by two additional three-day testing windows in Bahrain prior to the season opener.

The strategic importance of this testing window cannot be overstated. For Ferrari, and likely every other team on the grid, these nine days represent a critical opportunity to identify reliability weak points, validate component durability, and implement corrective measures before racing commences. Vasseur emphasized this point directly: "If you understand something [only] in Bahrain T02 [the final test], you won't have time to react for Australia". This statement encapsulates the entire reliability equation for 2026—early diagnosis is essential because the window for remediation is narrow, and the complexity of the new power units means that "quick fixes" are a thing of the past.

The 2026 scenario bears striking parallels to previous regulation changes that produced mechanical chaos and reshaped competitive hierarchies. Vasseur specifically referenced the era of 10-15 years ago, when early-season races routinely featured "a huge percentage of DNFs". These were the seasons when engine reliability, gearbox durability, and hydraulic system integrity determined outcomes as much as outright pace—when teams that managed to keep their drivers ahead of the safety car and running until the checkered flag ultimately claimed championships.

The 2022 regulation change offers a more recent parallel. That season introduced entirely new aerodynamic philosophies with ground effect elements and produced a development war that dramatically altered the competitive picture between the opening test and the final race. The difference was that 2022's power units carried over from 2021, providing a known quantity in the reliability equation. In 2026, no such safety net exists. The hybrid systems will be substantially different, requiring teams to develop intuition about failure modes, thermal management, and electrical system behavior that simply cannot be anticipated entirely through simulation.

Adding another layer of complexity, Vasseur anticipates an exceptionally aggressive upgrade trajectory throughout the 2026 season. "You will have a huge rate of development over the season, and more like 2022 or this kind of season," he explained, suggesting that the basic reliability foundation established during testing will form just the starting point for a relentless evolution campaign.

This means teams must simultaneously address multiple objectives:

This dual challenge—proving reliability while remaining competitive in the development arms race—may ultimately separate the organizational capabilities of the grid's elite teams from those with more limited resources. Teams with sophisticated simulation capabilities, extensive testing infrastructure, and deep benches of engineering talent will be positioned to extract reliability from their power units and chassis while simultaneously developing competitive upgrade packages. Teams lacking these resources may find themselves trapped in a frustrating cycle: unable to prove reliability without mileage, unable to accumulate mileage without reliability, and unable to catch up in the development race due to time spent addressing basic functionality.

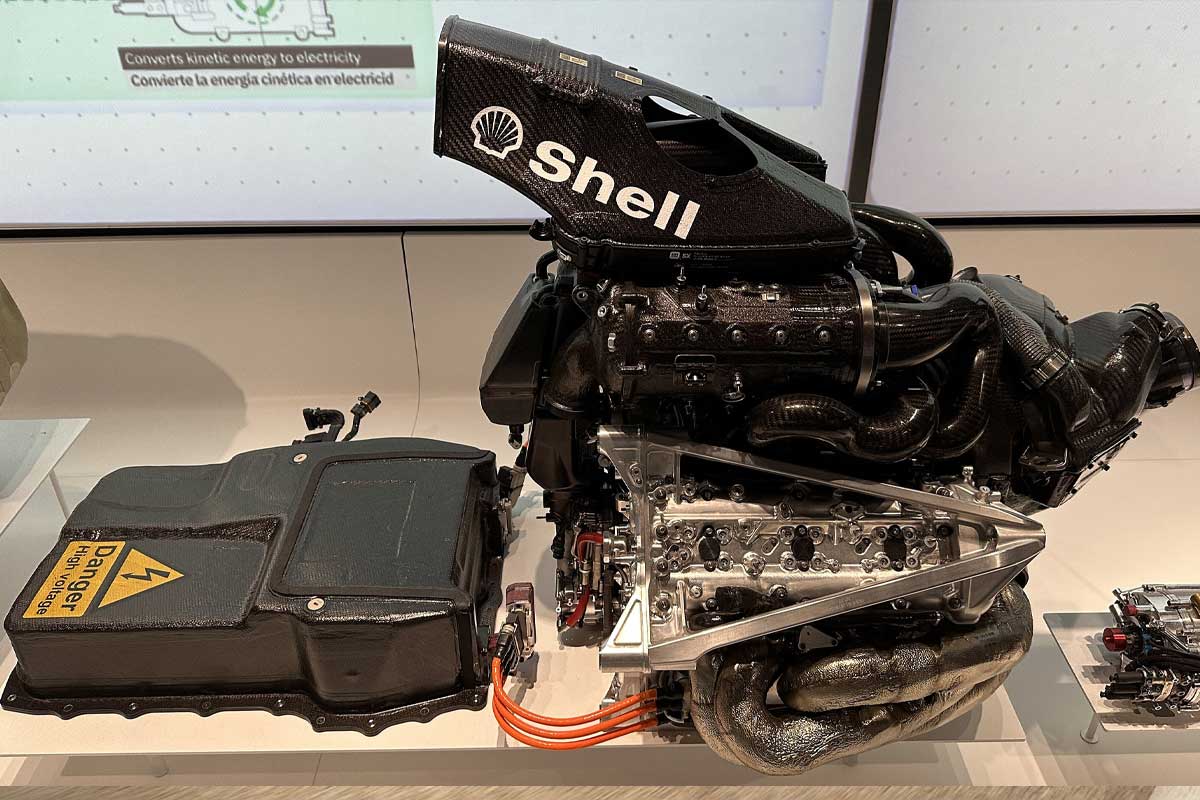

The 2026 Power Unit (PU) is perhaps the greatest source of anxiety for engineers. By removing the MGU-H (Motor Generator Unit - Heat) and significantly increasing the output of the MGU-K (Motor Generator Unit - Kinetic), the FIA has shifted the burden of performance onto the battery and the electrical recovery systems. This creates a massive thermal management challenge.

In previous years, the MGU-H helped manage turbocharger speeds and heat. Without it, the internal combustion engine (ICE) must work in a different rev range, and the battery must handle significantly higher discharge and charge rates. If a team pushes the battery too hard to find lap time, they risk thermal runaway or internal degradation. If they are too conservative, they will be "clipping" (running out of electrical boost) halfway down the straights. Finding the "sweet spot" where the car is both fast and capable of finishing 24 races is the puzzle every technical director is currently trying to solve.

The potential for reliability to reshuffle the competitive order represents one of 2026's great wildcards. Historically, regulation changes have been the most common catalyst for shifting the championship battle's geography around the grid. McLaren's resurgence in 2024 came not from revolutionary innovation but from steady, competent development of a fundamentally sound concept. Similarly, teams that have managed regulation transitions most effectively typically share common traits: conservative initial philosophies, robust manufacturing processes, and comprehensive testing programs.

In 2026, these characteristics will prove invaluable. The team that delivers a 95-percent-reliable car that finishes every race will accumulate far more championship points than the team that deploys a 90-percent-reliable car that's marginally faster but prone to failures. Early-season DNFs don't merely cost individual race results; they cost valuable development data, forcing teams to chase their most competitive rivals throughout the campaign. Vasseur's reference to Ferrari's past setbacks illustrates this principle—a single setback early in the season can create a cascading effect that consumes resources and reference points through the remainder of the year.

As teams finalize their 2026 designs and prepare for the January testing window, reliability has genuinely become the central design principle. Ferrari's deliberate "spec A" strategy represents this shift in thinking—a willingness to sacrifice marginal performance gains in pursuit of comprehensive reliability validation. Other teams, though perhaps not broadcasting this philosophy as openly, are almost certainly embracing similar principles.

The 2026 season will tell whether reliability truly emerges as the differentiator. History suggests it will. The introduction of new power units, fresh aerodynamic concepts, and unfamiliar mechanical architectures typically produces a season where the fundamentals—building cars that complete races—matter as much as the optimization. Teams that master this balance will find themselves with a significant advantage when the field arrives in Melbourne for the Australian Grand Prix, and potentially throughout a season where the competitive picture is expected to evolve dramatically.

For fans accustomed to a modern era where reliability is a given, 2026 may reintroduce an old variable into the championship equation—one that could prove every bit as decisive as driver talent or aerodynamic efficiency. The winner of the 2026 title might not be the team with the fastest car in February, but the team with the most robust car in November.

He’s a software engineer with a deep passion for Formula 1 and motorsport. He co-founded Formula Live Pulse to make live telemetry and race insights accessible, visual, and easy to follow.