As the Formula 1 circus prepares for the most significant regulatory shift in a generation, a familiar ghost has returned to haunt the design offices of Milton Keynes, Brackley, and Maranello: the battle against the scales. With the 2026 pre-season testing window appearing on the horizon, the paddock is buzzing with a singular, anxiety-inducing realization—the FIA’s ambitious "nimble car" concept is clashing violently with the laws of physics.

The mandate for 2026 was clear: reverse the trend of "obese" Grand Prix cars. However, early simulations and chassis builds suggest that teams are finding the new 768kg minimum weight limit not just challenging, but "brutally difficult" to achieve. With some designs reportedly sitting 15kg or more over the limit, the sport faces a technical crisis that could define the competitive order for years to come.

For over a decade, drivers and fans alike have lamented the increasing bulk of Formula 1 machinery. The transition to hybrid power units in 2014, followed by the wider, high-downforce cars of 2017 and the safety-heavy 2022 ground-effect era, saw minimum weights balloon from 642kg to a staggering 800kg.

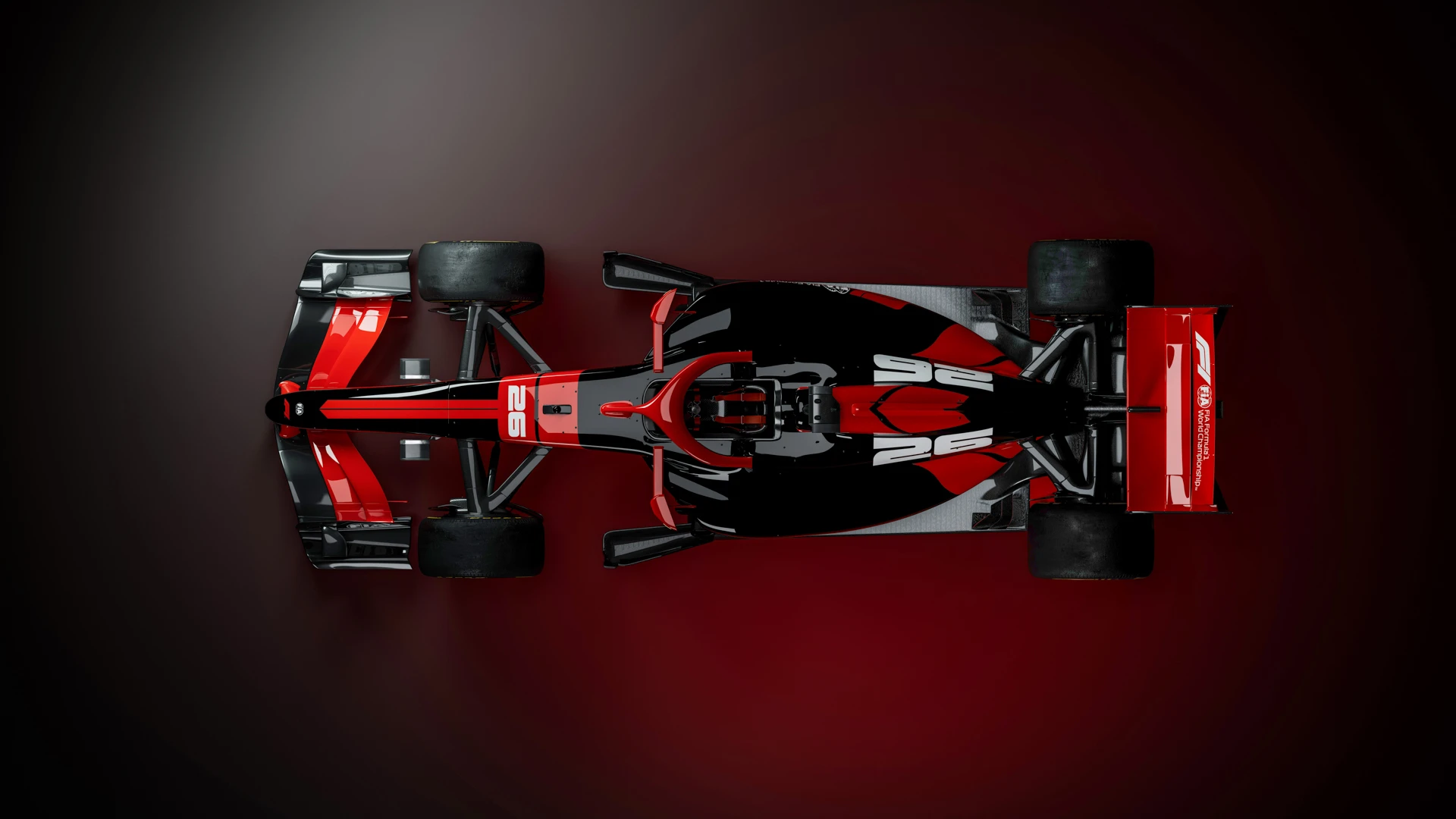

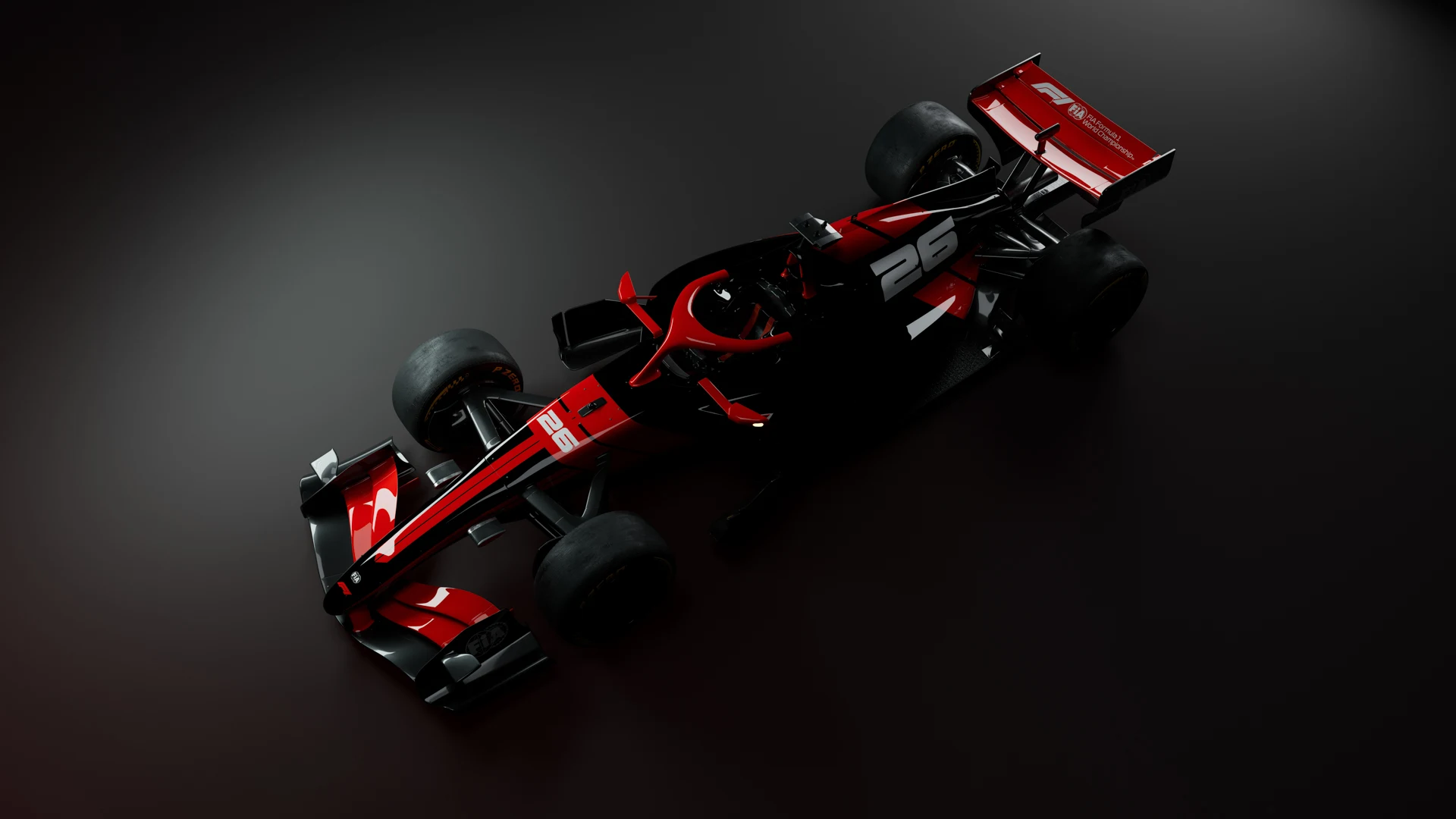

In response, the FIA’s 2026 regulations aimed to trim the fat. The "Nimble Car" concept centers on a significant reduction in dimensions and mass:

On paper, these changes represent a masterclass in downsizing. By shrinking the footprint of the car, the FIA hoped to naturally shed weight. However, the engineering reality of the 2026 Power Unit (PU) has thrown a massive wrench into these calculations.

The primary culprit behind the weight struggle is the 2026 Power Unit. While the complex MGU-H (Motor Generator Unit – Heat) has been removed to simplify the engines and attract new manufacturers like Audi and Ford, the electrical side of the hybrid system has been supercharged.

The new units demand a near 50/50 split between internal combustion and electric power. The MGU-K (Motor Generator Unit – Kinetic) will now produce 350kW of power, a massive leap from the current 120kW. To support this nearly threefold increase in electrical deployment, the cars require significantly larger and more robust battery systems.

As technical insiders have noted, the increased electrical deployment requires larger, heavier batteries that effectively offset the weight gains achieved through the smaller chassis and aerodynamic surfaces. Teams are essentially trying to fit a heavier "heart" into a smaller "body," creating a packaging and mass distribution nightmare.

In Formula 1, weight is the ultimate performance killer. The general rule of thumb in the paddock is that every 10kg of excess weight costs approximately 0.3 seconds per lap, depending on the circuit layout.

If current reports are accurate and some teams are indeed 15kg over the 768kg limit, they are entering the 2026 season with a built-in deficit of nearly half a second per lap. In a sport where the top ten are often separated by less than that margin, being overweight is a death sentence for championship aspirations.

Red Bull Racing’s Team Principal, Christian Horner, has been vocal about the arbitrary nature of the target. Horner argued that the 768kg figure was "plucked out of the air" without a full understanding of the weight penalties associated with the new power units. He warned that the challenge of hitting the target while maintaining structural integrity and safety would be "enormous" for every team on the grid.

Compounding the weight issue is the FIA’s refusal to compromise on safety. The 2026 cars will feature enhanced safety structures, including:

Remarkably, the FIA claims these safety improvements have been integrated without adding weight to the overall car. While this is a feat of engineering, it leaves teams with zero "fat" to trim from the safety structures. Every gram must now be saved from the suspension, the gearbox casing, or the intricate aerodynamic carbon fiber—areas that are already pushed to their absolute limits.

In previous eras, a team struggling with an overweight car would simply "spend" their way out of the problem. They would commission exotic, ultra-lightweight materials, redesign entire suspension assemblies in titanium, or manufacture dozens of different floor iterations to find the lightest weave.

In 2026, the Financial Regulations (the Cost Cap) make this impossible. Teams must choose their battles. Do they spend their limited budget on a massive weight-reduction program, or do they focus on aerodynamic development and power unit integration?

This creates a strategic divergence. A team like Mercedes, led by Technical Director James Allison, has suggested that the minimum weight should be difficult to hit. Allison argues that a challenging weight limit forces teams to make tough decisions and prevents the cars from becoming "lazy" designs. However, for teams further down the grid with less manufacturing infrastructure, a "brutally difficult" weight target could result in a permanent performance ceiling.

To compensate for the reduced downforce and the unique power delivery of the 2026 engines, the cars will feature sophisticated active aerodynamics. This includes movable front and rear wings that switch between "Z-mode" (high downforce for corners) and "X-mode" (low drag for straights).

While active aero is essential for the 2026 concept to work, it adds another layer of mechanical complexity—and weight. The actuators, hydraulics, and sensors required to move these wings reliably at 200mph add kilograms that the 2025 cars simply don't have to carry. It is another example of the "regulatory tug-of-war" where every new feature adds mass, while the rules demand the car get lighter.

As pre-season testing in Barcelona approaches, the tension in the paddock is palpable. History suggests that when the majority of teams struggle to hit a weight target, the FIA eventually relents and raises the minimum limit. We saw this in 2022, when the limit was raised by 3kg at the last minute to accommodate the reality of the new ground-effect cars.

However, the FIA’s Single-Seater Director, Nikolas Tombazis, has signaled a tougher stance for 2026. He has stated that the FIA does not want to "haggle" over weight and that the 768kg target is intended to be a "stretch goal" that rewards the most efficient engineering.

The 2026 weight crisis is more than just a technical hurdle; it is a fundamental test of the new Formula 1 ecosystem. It pits the FIA’s vision of smaller, more agile racing against the heavy reality of high-output electrification and stringent safety standards, all under the watchful eye of the cost cap.

As we head toward the first shakedowns, the teams that have mastered the art of "lightweighting" without sacrificing reliability will hold the keys to the kingdom. For those currently 15kg over the limit, the next few months will be a frantic, expensive, and perhaps futile race to shed mass.

One thing is certain: the 2026 season won't just be won in the wind tunnel or on the test bench—it will be won on the scales.

He’s a software engineer with a deep passion for Formula 1 and motorsport. He co-founded Formula Live Pulse to make live telemetry and race insights accessible, visual, and easy to follow.