When Lawrence Stroll committed billions to transform Aston Martin into a Formula 1 championship contender, the narrative seemed straightforward: hire the greatest car designer in the sport's history, combine it with substantial financial resources, and championship success would inevitably follow.

Yet as the 2026 season looms just two weeks away, that carefully constructed narrative has begun to crumble spectacularly. With the Australian Grand Prix set for March 8th in Melbourne, Aston Martin finds itself in the most precarious position imaginable—frantically searching for answers while the clock counts down to the first race.

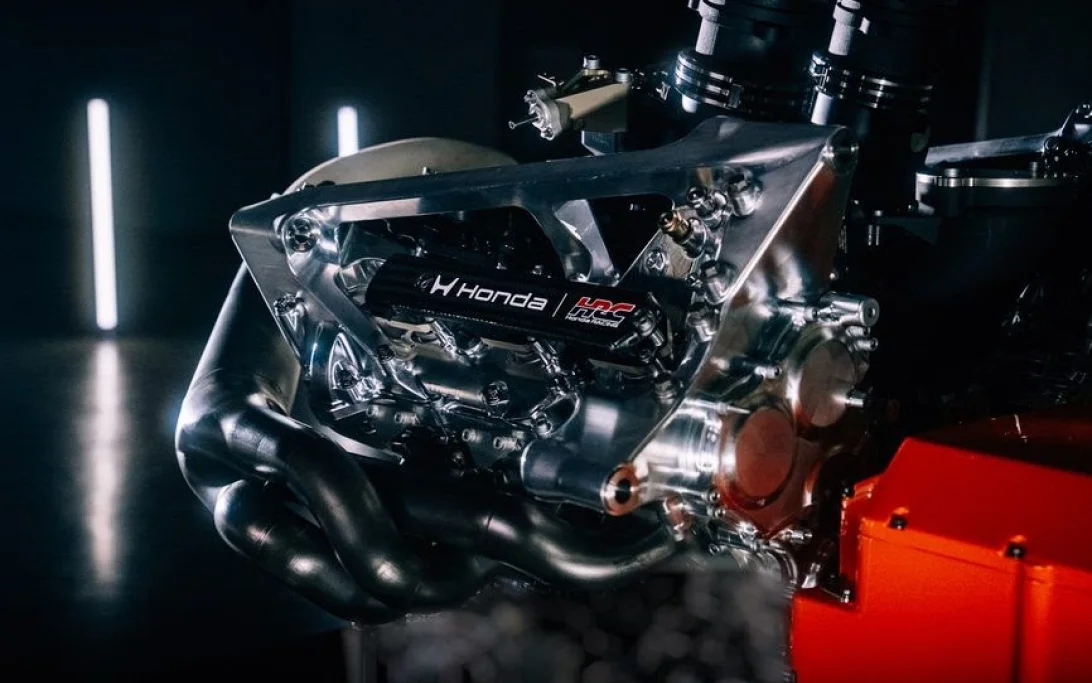

The team's struggles extend far beyond typical pre-season teething problems. This is a crisis born from an unfortunate confluence of circumstances: late access to development resources, a maturing partnership with Honda that appears fundamentally unprepared for the challenge, and the pressure of delivering results with one of motorsport's most celebrated engineers at the helm.

For Adrian Newey, whose career has been defined by dominance and precision, the AMR26 represents not just another car project, but potentially a defining moment that will determine whether his legendary status can transcend the specific technical environments in which he achieved his greatest success.

The story of Aston Martin's 2026 struggles begins not in Bahrain or Barcelona, but in the seemingly bureaucratic timeline of F1 regulations. Under 2026 rules, teams were permitted to commence aerodynamic testing on the new generation of cars in early January 2025. For established teams like Mercedes, Ferrari, and McLaren, this represented an opportunity to immediately begin the intricate process of building and refining their wind tunnel models. However, Aston Martin's head start never materialized.

Adrian Newey's arrival at Aston Martin came in March 2025—three months after aerodynamic development officially began. This timing, while seemingly manageable on paper, proved catastrophic in practice. The CoreWeave Wind Tunnel at Aston Martin's AMR Technology Campus, despite its state-of-the-art credentials, wasn't operational until April 2025. Consequently, the AMR26's first wind tunnel model didn't materialize until mid-April, creating a staggering four-month development gap between Aston Martin and its competitors.

Newey himself acknowledged the severity of this handicap: "The reality is that we didn't get a model of the '26 car into the wind tunnel until mid-April, whereas most, if not all of our rivals would have had a model in the wind tunnel from the moment the 2026 aero testing ban ended at the beginning of January last year. That put us on the back foot by about four months."

In Formula 1, where marginal gains are measured in thousandths of a second and development cycles are measured in months, a four-month deficit isn't simply a setback—it's a structural disadvantage that compounds exponentially. This wasn't a matter of coming to Barcelona or Bahrain slightly behind schedule. This was a matter of being forced to compress an entire season's worth of development work into a matter of weeks.

When the AMR26 finally made its public debut at the Barcelona shakedown test in late February 2026, the reaction was decidedly mixed. The car's aggressive design language—particularly its unconventional suspension mounting points and tightly packaged sidepods—immediately caught the attention of rival teams and media observers. Mercedes driver George Russell, who will battle for this year's drivers' championship, described it as "probably the most standout in terms of the car design," though he wisely noted that aesthetic boldness means nothing if the car lacks pace.

However, the Barcelona appearance itself highlighted Aston Martin's predicament. The team didn't arrive until the penultimate day of testing, struggling to complete final assembly and system checks. More troublingly, the AMR26 managed only 65 laps across the entire Barcelona shakedown—a stark contrast to Mercedes' 502 laps. This wasn't simply a case of different team philosophies regarding testing programs. This was a team fighting against time simply to get its machinery operational.

Newey revealed the car had "only came together at the last minute, which is why we were fighting to make it to the Barcelona shakedown," a statement that should have served as a clear warning of the turbulence ahead. Yet despite these concerns, there remained a thread of optimism. Newey's design philosophy—emphasizing fundamental principles and long-term development potential rather than immediate optimization—suggested that early pace wasn't necessarily indicative of seasonal trajectory.

This optimism would prove premature.

The first week of formal pre-season testing in Bahrain exposed the true extent of Aston Martin's problems. Lance Stroll, partnered with two-time world champion Fernando Alonso, provided devastatingly honest assessments of the situation. "The bottom line is we are slow. We are not where we want to be," Stroll stated plainly. More specifically, he quantified the gap: Aston Martin appeared to be approximately four seconds off the pace of the leading teams.

In isolation, a four-second deficit in February testing might be considered addressable through development and optimization. In context, it's catastrophic. These aren't the early laps of a rookie driver or a fundamentally flawed aero philosophy. This is the measured gap between a car that has received nearly a full season of development and one that has received barely four months of concentrated work.

Alonso's assessment mirrored his younger teammate's concerns. "We need more performance," the Spanish legend stated succinctly, a remarkable understatement given the magnitude of the problem. But the greatest blow came not from pace deficits, but from reliability failures.

As the second week of Bahrain testing unfolded, a far more ominous problem emerged—one that transcended aerodynamic refinement or suspension tuning. Aston Martin's engine partner, Honda, revealed that the power unit was suffering from battery-related reliability issues. On Thursday, Alonso was forced to exit the car when mechanical issues threatened its structural integrity, with mechanics required to handle the chassis with special care. By Friday, Honda made a stunning decision: the engine manufacturer would limit its running, eventually pulling Stroll from the car entirely after just six laps.

The implications were staggering. Honda wasn't simply struggling with performance—a concerning problem in itself, given the vast performance disparity this early in the season. Rather, the manufacturer faced fundamental reliability issues that could compromise budget allocation and battery supply for the remainder of the season. Honda's decision to stop testing wasn't a confidence-boosting pause for fine-tuning. It was a triage measure designed to preserve limited resources until critical issues could be resolved.

Spanish F1 commentator Antonio Lobato synthesized the crisis bluntly: "Honda has a problem, presumably localised, that breaks the battery. As the problem cannot be solved in Bahrain, Japan is asking not to race so as not to use up more batteries, which would compromise future races and the budget limit that the engine manufacturers also have."

This presented an extraordinary situation: Aston Martin was arriving at the first race of the season having barely tested its power unit, still four months developmentally behind its rivals, with a propulsion partner that had already signaled significant limitations to overcome. Yet Lobato's analysis also contained a thread of possibility: "If Honda does its homework and Newey lives up to his genius profile, Aston Martin could shine in the second half of the season."

To understand the weight of expectation pressing down on Aston Martin—and Adrian Newey specifically—requires acknowledging the designer's extraordinary track record. Newey is, quite simply, the most successful car designer in Formula 1 history. His designs have yielded 25 championships across his career at March, McLaren, Ferrari, and Red Bull. His ability to reimagine technical regulations, exploit loopholes within the rules, and design cars that are simultaneously beautiful and devastatingly effective has defined multiple eras of the sport.

At Red Bull, Newey designed the RB5 and RB6 that sparked the team's first championships. Later, the RB8, RB9, and RB10 continued a streak of dominance that redefined expectations for technical innovation in Formula 1. His designs have consistently featured elements that seemed impossible before he conceived them—innovations that subsequently became standard within the paddock.

Against this backdrop, the AMR26's struggles carry particular weight. This is Newey's first fully realized design for a new regulation era in a team other than Red Bull. More importantly, for the first time in his career, Newey is operating without the luxury of unlimited development time and resources. He joined a team mid-development cycle, tasked with salvaging a project that had already lost four months of momentum. The pressure to justify his €30+ million annual salary and his unparalleled reputation is immense.

Despite the immediate crisis, Aston Martin's leadership maintains a longer-term perspective. The team has publicly framed its title ambitions as a 10-year project, positioning themselves at approximately the halfway point in this timeline. This framing attempts to contextualize short-term struggles within a broader strategic vision—a narrative that, while theoretically sound, becomes increasingly difficult to sustain with each disappointing test session.

The team possesses undeniable advantages: adequate financial resources, access to Newey's intellectual capital, competitive drivers in Fernando Alonso and Lance Stroll, and the infrastructure of the new AMR Technology Campus. Yet advantages mean nothing if they cannot be deployed effectively. And currently, the machinery simply isn't delivering.

Aston Martin will arrive at the Australian Grand Prix having virtually no recent testing data with a fully reliable power unit. The team will be among the least prepared grids in recent F1 history. Lance Stroll and Fernando Alonso will pilot a car that, by most accounts, is significantly off the pace of Mercedes, Ferrari, McLaren, and likely several other competitors. Honda will field an engine that has demonstrated fundamental reliability concerns just days before the season commences.

Yet the season stretches across 24 races. Development opportunities exist at nearly every venue. While the early races may prove torturous, the second half of the season could theoretically permit significant improvement—provided Honda resolves its power unit issues and Newey's fundamental design principles bear fruit as development unfolds.

The question posed—"Is this the end?"—can only be answered with uncertainty. For Aston Martin, this is undoubtedly a make-or-break season. For Adrian Newey, it represents perhaps his most significant professional test: can his legendary design intellect overcome structural disadvantages and partner incompetence to deliver competitive results?

The answer will become apparent in Melbourne, and fully understood only in the months that follow.

He’s a software engineer with a deep passion for Formula 1 and motorsport. He co-founded Formula Live Pulse to make live telemetry and race insights accessible, visual, and easy to follow.

Want to add a comment? Download our app to join the conversation!

Comments

No comments yet

Be the first to share your thoughts!